Old Bookaroo

Silver Member

- Dec 4, 2008

- 4,318

- 3,510

Lost Mines

By G. L. Sheldon [Ely, Nevada]

By G. L. Sheldon [Ely, Nevada]

Lost mines! Who has not felt the lure of the mystic combination of these two- simple words? The gambling spirit is inherent in the human race; and in the search for lost mines and buried treasure the prospector and the average man may find a fascinating field for indulging this propensity, each in the hope that fortune will smile upon him. It is a legitimate sport, however, and the fellow who outfits a prospector for such a venture should bear in mind that the latter frequently risks that which is more precious than a few hundred dollars in cash—sometimes his very life.

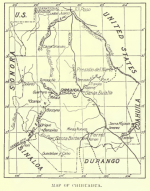

In the United States the lost-mine industry appears to offer less chance of reward than in Mexico and South America. In Mexico, practically every mining district can boast of its lost mine. Many of these, no doubt, actually exist, for the reason that about 100 years ago the Indians, fired by the enthusiasm of the priest Hidalgo, either massacred their Spanish taskmasters or drove them from the country. The Indians, attributing their enslavement to the Spaniards' lust for gold and silver, covered up, caved or destroyed the entrances to many of the mines. Assisted by nature in a country where torrential rains abound at certain seasons, it is not surprising if the Indians in many eases succeeded in obliterating all local clues to the location of mines which once sent their Royal Fifth to enrich the King of Spain or his viceroys.

The records, however, remain in distant archives, telling, in many instances, the names of the mines, the district where located, the production at different times, etc., but rarely is the description of a character to enable the casual searcher to rediscover them.

One of the most noted—Topia—supposed to be in the southeastern part of Sonora or over the line in western Chihuahua, is said to have been fabulously rich and to have had a large production. It has been stated that records describe a trail hewn out of perpendicular cliff for several hundred feet, then a certain distance across a mesa, where there are two piles of rocks or monuments, with a cross between them. Thence, go in the direction which one of the arms of the cross indicates to a small circular valley in which is situated the town, and mine, Topia.

Many Americans and Mexicans have spent much time and money hunting for this mine. Often has it been reported as found, but subsequently developments have proved that a mistake was made. It is even stated that President Diaz at one time had 40 to 50 soldiers out several months trying to find it.

One day my mozo, while hunting deer, found an old trail, cut out of the rocks in places and leading up into the mountains in the section where the Topia mine is supposed to be situated. It was in a wild, isolated country and must have been made to give access to a mine. But as we were scheduled to break camp in a day or two, it was not investigated.

An American of my acquaintance who once explored in this locality described to me what bears a close resemblance to the identical trail. He stated that he and his companions went over the line into Chihuahua, climbing a trail which in places was cut out of the solid rock. The trail must, indeed, have been an ancient one, for the drill-holes, cut in the rocks to receive the hard-wood pins which served to hold in place the logs forming the outer edge of the trail in the most dangerous places, were evidently made with a flint rock and not with iron or steel, as they were about 3 and 4 in. in diameter.

On the mesa above they found the two piles of rocks with a cross between them. Following the direction in which one of the arms of the cross pointed, they came to a circular valley. Here was abundant evidence of an old town, and a large one, some of the ruins indicating that the houses must have been at least 100 ft. square.

But a group of Indians resented the presence of the intruders, directing a few shots at them and setting fire to the underbrush. As it was during the dry season, the fire spread so rapidly that my friend and his party suddenly remembered a pressing engagement somewhere else and never returned. Nor have I ever investigated this territory since, though my friend gave me the directions for finding the locality.

When operating in southwestern Chihuahua our hacienda was near the junction of two small creeks in an old mining district. In the early days it was the custom of the Government to coin silver slugs for use as money in each locality, these slugs weighing as high as 10, 20, 50 and 100 oz. When we first went there in 1898, small pieces of silver bullion, from 1 to 10 oz., circulated as money at one peso per ounce, and, small change being scarce, the merchants would stamp the weight on each piece.

On a small creek which headed just below two old silver mines the natives would at the close of the rainy season wash the gravel to recover native silver, using the wooden batea in the same manner as it is employed in placer mining for gold. When a few ounces of silver had been secured they would place it in a fragment of broken olla (the general utility article of culinary pottery employed throughout Spanish America) with some lead flux and smelt it crudely in the charcoal fire of a blacksmith's forge, scorifying the charge and recovering a single lump of silver bullion ranging from 975 upward in fineness.

On our hacienda there was a large boulder about 20 ft. high and flat on the top. Tradition had it that the Jesuit priests used it as a pulpit from which to preach to the Indians. One day, while setting out banana plants in the vicinity of this boulder, we found a floor about a foot below the surface. Not far from this we discovered the ruins of several old adobe rasos, or crude smelting plants, as well as pieces of ore.

Several were found in this immediate neighborhood, indicating the former activity of Indians and Spaniards—notably a stone measuring about 2x3x4 in. with a groove at each extremity (presumably employed by the Indians in the manufacture of arrows) and an old spur of the type used by the soldiers of Cortez and Coronado, with a rowel wheel about 7 in. in diameter.

Here were evidences of an old trail leading up into the mountains from our hacienda. In places the trail was cut out of the solid rock. There was no known pass leading out or across the mountains in this direction. Therefore it is probable that it led to a mine or something equally interesting.

Although tradition (whose alias in Spanish America is se dice, or "they say") speaks of an old lost mine in that section, neither Americans nor Mexicans are known to have found it. A few years before I went there a boy lost his way while hunting cattle and found an old mine dump. Some pieces of ore, said to be from the dump in question, were assayed by an American and found to be rich in silver. The American, with the boy and other Mexicans, spent several days trying to find the old dump again, but the search was fruitless.

In southwestern Chihuahua, a few miles from the state line, there is a small rolling mountain of limited extent concerning which it is said that the records in Spain show that the old Gloria Pan (either "heavenly bread," "communion bread"' or "cream-cake") mine is located upon it, that it was rich in native silver and that it had a large production. Many people (including a Mexican of my acquaintance, who with several men spent two months in the search) have tried to find it, but with the usual result. On a creek at the foot of the mountain are the ruins of an old hacienda, and pieces of ore showing native silver have been found there.

Not far from these old ruins is a trail starting up the mountain ; but a landslide or some other convulsion of nature has cut the trail off abruptly.

We were operating not far from this mountain, having located a zone with the exclusive right to prospect the mountain for 90 days. We had two Americans prospecting there for nearly two months. One doctored the sick child of an Indian who lived in the vicinity. The father of the child brought this American a piece of ore showing native silver, saying that it was from the Gloria Pan mine and that out of gratitude for the curing of the child he would show the location of the mine. But for some reason he failed to keep his promise.

The Jesuit priests in the early days of the conquest of the Americas (and ever since) have taught the Indians that all mines belonged to God, were only for His use and that, if they showed the mines to anyone but the priests God would be angry and would strike them dead either immediately or soon thereafter. This grim and astute warning has so impressed the Indians for generations that it is almost a waste of time to attempt to induce an Indian to show a mine. Many an American has learned this to his cost.

However, I learned of one apparently authentic case. My mozo (who was afterward with me for 10 years, and whom I consider to be absolutely reliable) was once accosted by an Indian with a high-tension thirst. This Indian had been drinking for several days and was out of funds, but apparently still obsessed with a suicidal mania and quite indifferent as to any choice between the Jesuit route and the plain alcoholic route. He said, or attempted to say, "Yo tengo una mina, hombre, muy rico. Dame una botella de mezcal y yo la ensenare a Ud." (I have a mine, mister, very rich. Give me a bottle of maguey brandy and I'll show it to you.) His request was grained, and the performance was repeated daily for six days, alter which the Indian vanished. A month later he reappeared and said, "Vamanos" { Come, let us go). They went out of town several miles to a mountain where the Indian had been cutting wood. The Indian sat on the ground, saying "Aqui esta su mina, muya rica. Buscala." (Here is your mine, very rich. Search for it.) He hunted all around, while the Indian remained seated in the same place, repeating the formula and moving his outstretched hands in a circle around him. After a few hours the mozo, not finding any signs of a vein, became disgusted and left, cussing the Indian.

Later, in thinking it over, he recalled that the Indian always had his thumbs pointed down toward the ground when moving his hands to and fro. He returned to the mountain, and in the spot where the Indian had been seated was a vein of rich silver ore covered with grass and leaves. He located it. His father was an expert millman and understood the "patio process,'' having worked many years for a rich Mexican, mining and milling ores. They worked the mine for a time, were doing well and had bought some cows and a small place with an orange grove.

One day the Mexican for whom his father had worked came to see the mine. He bought it, ostensibly for $21,000—$l000 cash and $20,000 in future payments. Neither my mozo nor his father could read or write. They signed the papers by making their mark, and later it transpired that they had sold the mine outright for the $1000. Up to a few years ago the mine was still working.

The rich Mexicans have often treated the poor peons in this manner; and this fact, no doubt, is one of the direct causes of the present conditions in that unhappy republic. It has often been the case that the peons would show us, the Americans, mines or veins because we have the reputation of playing fair. We should strive to live up to our reputation.

In the near vicinity of the mountain where the Gloria Pan mine is supposed to lie located is a creek cutting through a massive, dense, soft gray porphyry. The action of the waters has cut out this porphyry in such a way that in places, while the opening at the plateau level is but 50 to 100 ft. wide, at the creek level, 200 to 300 ft. below, there is a width of 200 to 300 ft., the ravine thus having overhanging smooth walls. There are places where these walls, well protected from the action of the elements, are painted in various bright colors. The designs depict many kinds of animals and birds, some of which can hardly be said to represent any types known to modern naturalists. A trained archaeologist, however, might construct some interesting theories to account for the origin of these pictures, proving some of his points by comparison with some far-distant but exactly similar records undreamed of by the casual prowler.

In general it may be stated that when the Mexican — who is a close observer—cannot find a lost mine it is almost useless for a white-man-in-a-hurry to spend his time looking for it. His feverish haste to get rich operates against him and blinds him to many things which might aid him in his search. Apparently, success in the quest for lost mines may be attained by but two classes of persons—the trained expert who is willing to devote his time to the systematic analysis of fascinating facts and the natural-born lucky fellow who is watched over by a divine Providence.

~ THE ENGINEERING & MINING JOURNAL 24 April 1915 ( Vol. 99, No. 17)

Note

“Scorifying” is the process of separating ore into valuable precious metal and refuse scoria – cinder-like slag or waste.

Good luck to all,

The Old Bookaroo

Last edited: