Gypsy Heart

Gold Member

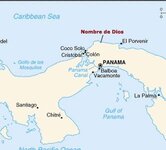

Nombre de Dios : 'In The Name of God' Buried Silver and Gold

In 1501 the Spaniards Rodrigo de Bastidas and Vasco Nuñez de Balboa sailed from Venezuela to explore the Caribbean coast of Panama as well. But it was Columbus who founded the town of Nombre de Dios; he was the first European to arrive and give the place a name. On this his final journey to the Americas, Columbus traveled with only four ships. The journey had not gone well, the ships had sailed through rough weather and the crew was tired and scared by the time they reached Nombre de Dios. And apparently so was Columbus: he said to his crew: “in the name of God we will go no further”. Hence the name of the town: Nombre de Dios (Name of God). The Indians in the hills above the Nombre de Dios came to greet Columbus’s four ships in the empty harbor; they were happy to trade cotton and food with the Spanish, but they had no gold for Columbus, of course that was what he was looking for: he had to return to Spain with something. Columbus left the settlement almost as soon as he arrived and sailed back in the direction of Costa Rica: he had seen gold in the Indian settlements near Costa Rica. Columbus would never return to Nombre de Dios.

In 1510 Diego de Nicuesa founded a permanent settlement at Nombre de Dios and then in 1519 the Spanish capital of Panama was moved from Santa María de la Antigua del Darién on the Caribbean coast to Panama City on the Pacific Coast; this was done because of the better weather and health conditions on the Pacific side. Panama – which means an abundance of fish - was the name of the new Pacific capitol and to connect the Pacific and Caribbean sides of Panama a road was built from Nombre de Dios to Panama City: the road became known as the Camino Real. The Camino Real was 50 miles long and nine feet wide at its widest points; beyond the nine feet of trail there was nothing but jungle and cimmarones and corsairs.

Cimmarones or as the English called them Maroons were black slaves that were able to break free from their Spanish masters and make their way into the jungle. Most of the slaves would have arrived in Nombre de Dios and then broken free there or along the Camino Real. The idea of breaking free from the Spanish and running into the jungle took great courage as the jungle must have been incredibly hard to navigate, since in the jungle you have no view of the horizon or static points in the far distance such as mountains or rivers. Also, the runaway slaves would have had no knowledge of the dangers one might encounter in the jungle or how to survive, and the maroons knew there were Indians living in the jungle that might be hostile to them. But even with all these difficulties the maroons, incredibly, were able to establish settlements in the jungle far from the Spanish. From these settlements in the jungle they learned to navigate the jungle and waterways better than the Spanish who were fearful of walking into jungle where they might be attacked or disappear in lost confusion. From their settlements in the jungle the maroons would run raids along the Camino Real in the dry season which was the only time of the year the Spanish moved gold and silver across the trail. The captured gold and silver was taken by the maroons, not because they treasured its value, but because it was for them a way to harass the hated Spanish who were known to be obsessed with gold and silver. Legend has it that the maroons buried the stolen gold and silver in river beds. The treasure could only be dug up when the dry season came and the streams narrowed.

Another danger on the Camino Real for the Spaniards was the corsairs: in this case the corsairs were French Huguenots that lived in the jungle near Nombre de Dios or sailed the seas east of the town. They knew the jungle and the habits of the Spanish and were able to carry out raids against the Spanish along the Camino Real and at sea. They were also friends of the English as were the maroons; the anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic sentiments created a very unlikely alliance between the French, Africans and English in Panama. The personality that brought these unlikely groups together in order to try to isolate Nombre de Dios from the Spanish and strip it of its gold and silver was the Englishman Francis Drake who landed in Panama in 1572.

.

Born in Devon in 1540-43, Drake seems to have been made to go to sea as he spent his youth sailing between Medway and Antwerp and other North Sea ports. His hatred for Catholicism and particularly the Spanish was extreme and was a product of his father’s teachings: his father was a harsh Protestant lay preacher. Those prejudices against Catholicism were radicalized further by the English disaster at San Juan de Ulua, Mexico. In 1568 at San Juan de Ulua, six British slave-trading ships were attacked by the Spanish while in harbor for repairs: only Drake and his cousin John Hawkins escaped. The incident led not only to Drake’s bitter hatred of Catholics and Spaniards, it also lead to the sinking of the Spanish Armada in 1588. The incident in Mexico triggered the rivalry between Spain and England for control of the seas. Drake became a kind of cult figure in Europe in the subsequent decades following his raids on Spain’s holdings in the New World. His piracy against the Spanish and the Catholic world made him a hero in those parts of Europe where the Reformation had gained strength. His successes at sea were the Protestant-world’s successes. He was a beloved figure in 16th century Protestant Europe. To his enemies he was a terrorist that threaten the security and wealth of the Catholic world. Though hated by Catholics, he was a well-respected figure by his adversaries because of his great abilities as a navigator. Much of the aristocracy in Europe was in awe of Drake: many desired a picture of him as a souvenir.

Drake took Nombre de Dios in July and August of 1572, but retreated out to sea after being shot in the leg. After retreating from Nombre de Dios, Drake settled on a rock island near the entrance of the harbor at Nombre de Dios, from there he calculated his next move. The Spanish tried to negotiate with Drake, but he refused; after turning the Spanish down, he disappeared from sight, out to sea or along the coast, no one in Nombre de Dios really knew. The inhabitants of the town were in mortal fear of Drake. Rumor and paranoia gripped the town and Panama.

With the help of some maroons who lived to the east of Nombre de Dios, Drake navigated his way through the jungles of Panama to the Pacific coast. Drake then carried out two raids on the Camino Real: the first raid was on the Pacific side, closer to modern day Panama City; the other, and more successful raid, took place in the hills above Nombre de Dios. The second raid was carried out with the help of a French Huguenot by the name of Captain Tetu and a maroon named Pedro who Drake had converted to Protestantism. Drake was able to capture £50,000 worth of silver and gold, a fortune for the time. Drake sailed back to England with the stolen treasure and on August 9th 1573 presented his treasure to Queen Elizabeth. After Drake’s raids on Panama the Spanish moved the Caribbean end of the Camino Real from Nombre de Dios to Portobello where nature provided a more secure port against pirates. Nombre de Dios languished and then disappeared under the shadow of Portobello.

For Drake this was just the beginning of his many adventures which would eventually take him around the world; he would sail the globe and in 1596, while trying to capture some of his old glory by raiding the Camino Real one last time, he would return to Panama where he died of fever in the town of Portobello. His dead body was submerged in the dark waters of the bay.

Excerpts taken from http://www.escapeartist.com/efam/69/Travels_To_Nombre_De_Dios.html

In 1501 the Spaniards Rodrigo de Bastidas and Vasco Nuñez de Balboa sailed from Venezuela to explore the Caribbean coast of Panama as well. But it was Columbus who founded the town of Nombre de Dios; he was the first European to arrive and give the place a name. On this his final journey to the Americas, Columbus traveled with only four ships. The journey had not gone well, the ships had sailed through rough weather and the crew was tired and scared by the time they reached Nombre de Dios. And apparently so was Columbus: he said to his crew: “in the name of God we will go no further”. Hence the name of the town: Nombre de Dios (Name of God). The Indians in the hills above the Nombre de Dios came to greet Columbus’s four ships in the empty harbor; they were happy to trade cotton and food with the Spanish, but they had no gold for Columbus, of course that was what he was looking for: he had to return to Spain with something. Columbus left the settlement almost as soon as he arrived and sailed back in the direction of Costa Rica: he had seen gold in the Indian settlements near Costa Rica. Columbus would never return to Nombre de Dios.

In 1510 Diego de Nicuesa founded a permanent settlement at Nombre de Dios and then in 1519 the Spanish capital of Panama was moved from Santa María de la Antigua del Darién on the Caribbean coast to Panama City on the Pacific Coast; this was done because of the better weather and health conditions on the Pacific side. Panama – which means an abundance of fish - was the name of the new Pacific capitol and to connect the Pacific and Caribbean sides of Panama a road was built from Nombre de Dios to Panama City: the road became known as the Camino Real. The Camino Real was 50 miles long and nine feet wide at its widest points; beyond the nine feet of trail there was nothing but jungle and cimmarones and corsairs.

Cimmarones or as the English called them Maroons were black slaves that were able to break free from their Spanish masters and make their way into the jungle. Most of the slaves would have arrived in Nombre de Dios and then broken free there or along the Camino Real. The idea of breaking free from the Spanish and running into the jungle took great courage as the jungle must have been incredibly hard to navigate, since in the jungle you have no view of the horizon or static points in the far distance such as mountains or rivers. Also, the runaway slaves would have had no knowledge of the dangers one might encounter in the jungle or how to survive, and the maroons knew there were Indians living in the jungle that might be hostile to them. But even with all these difficulties the maroons, incredibly, were able to establish settlements in the jungle far from the Spanish. From these settlements in the jungle they learned to navigate the jungle and waterways better than the Spanish who were fearful of walking into jungle where they might be attacked or disappear in lost confusion. From their settlements in the jungle the maroons would run raids along the Camino Real in the dry season which was the only time of the year the Spanish moved gold and silver across the trail. The captured gold and silver was taken by the maroons, not because they treasured its value, but because it was for them a way to harass the hated Spanish who were known to be obsessed with gold and silver. Legend has it that the maroons buried the stolen gold and silver in river beds. The treasure could only be dug up when the dry season came and the streams narrowed.

Another danger on the Camino Real for the Spaniards was the corsairs: in this case the corsairs were French Huguenots that lived in the jungle near Nombre de Dios or sailed the seas east of the town. They knew the jungle and the habits of the Spanish and were able to carry out raids against the Spanish along the Camino Real and at sea. They were also friends of the English as were the maroons; the anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic sentiments created a very unlikely alliance between the French, Africans and English in Panama. The personality that brought these unlikely groups together in order to try to isolate Nombre de Dios from the Spanish and strip it of its gold and silver was the Englishman Francis Drake who landed in Panama in 1572.

.

Born in Devon in 1540-43, Drake seems to have been made to go to sea as he spent his youth sailing between Medway and Antwerp and other North Sea ports. His hatred for Catholicism and particularly the Spanish was extreme and was a product of his father’s teachings: his father was a harsh Protestant lay preacher. Those prejudices against Catholicism were radicalized further by the English disaster at San Juan de Ulua, Mexico. In 1568 at San Juan de Ulua, six British slave-trading ships were attacked by the Spanish while in harbor for repairs: only Drake and his cousin John Hawkins escaped. The incident led not only to Drake’s bitter hatred of Catholics and Spaniards, it also lead to the sinking of the Spanish Armada in 1588. The incident in Mexico triggered the rivalry between Spain and England for control of the seas. Drake became a kind of cult figure in Europe in the subsequent decades following his raids on Spain’s holdings in the New World. His piracy against the Spanish and the Catholic world made him a hero in those parts of Europe where the Reformation had gained strength. His successes at sea were the Protestant-world’s successes. He was a beloved figure in 16th century Protestant Europe. To his enemies he was a terrorist that threaten the security and wealth of the Catholic world. Though hated by Catholics, he was a well-respected figure by his adversaries because of his great abilities as a navigator. Much of the aristocracy in Europe was in awe of Drake: many desired a picture of him as a souvenir.

Drake took Nombre de Dios in July and August of 1572, but retreated out to sea after being shot in the leg. After retreating from Nombre de Dios, Drake settled on a rock island near the entrance of the harbor at Nombre de Dios, from there he calculated his next move. The Spanish tried to negotiate with Drake, but he refused; after turning the Spanish down, he disappeared from sight, out to sea or along the coast, no one in Nombre de Dios really knew. The inhabitants of the town were in mortal fear of Drake. Rumor and paranoia gripped the town and Panama.

With the help of some maroons who lived to the east of Nombre de Dios, Drake navigated his way through the jungles of Panama to the Pacific coast. Drake then carried out two raids on the Camino Real: the first raid was on the Pacific side, closer to modern day Panama City; the other, and more successful raid, took place in the hills above Nombre de Dios. The second raid was carried out with the help of a French Huguenot by the name of Captain Tetu and a maroon named Pedro who Drake had converted to Protestantism. Drake was able to capture £50,000 worth of silver and gold, a fortune for the time. Drake sailed back to England with the stolen treasure and on August 9th 1573 presented his treasure to Queen Elizabeth. After Drake’s raids on Panama the Spanish moved the Caribbean end of the Camino Real from Nombre de Dios to Portobello where nature provided a more secure port against pirates. Nombre de Dios languished and then disappeared under the shadow of Portobello.

For Drake this was just the beginning of his many adventures which would eventually take him around the world; he would sail the globe and in 1596, while trying to capture some of his old glory by raiding the Camino Real one last time, he would return to Panama where he died of fever in the town of Portobello. His dead body was submerged in the dark waters of the bay.

Excerpts taken from http://www.escapeartist.com/efam/69/Travels_To_Nombre_De_Dios.html