1834 Granger, Wyoming

N41° 35' 14.3" W109° 58' 35.9"

Nathaniel Wyeth left Independence on April 28, 1834, with Milton Sublette, Jason Lee, a Methodist minister, and two naturalists, Thomas Nuttall and Kirk Townsend, plus seventy-five other men and two hundred and fifty horses. When William Sublette learned of the arrangement between Fitzpatrick and Wyeth, he left a few days later. Sublette over took Wyeth and passed him during the night. When Sublette reached Laramie Creek near where it empties into the North Platte River, he left several men to start construction on Fort William (Fort Laramie).

Once at the rendezvous, Sublette forced Fitzpatrick to buy his supplies from him; he still held notes on the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. When Wyeth arrived a few days later, he noted:

...and much to my astonishment the goods which I had contracted to bring to the Rocky Mountain Fur Co. were refused by these honorable gentlemen.

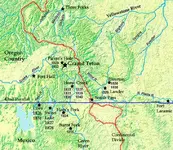

The suppliers at the rendezvous were the American Fur Company, Sublette and Campbell, and Nathaniel Wyeth. The American Fur Company was camped near the junction of Ham's Fork and Blacks Fork where the above picture was taken. Sublette and the Rocky Mountain Fur Company were five to ten miles up Ham's Fork and Wyeth was another five or so miles above them.

After the rendezvous, a disgruntled Wyeth took his supplies to the Portneuf River near its junction with Snake River and built Fort Hall. Wyeth sold Fort Hall to the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1835.

At the end of the 1834 rendezvous on Ham's Fork, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company was dissolved and a new company Fontenelle and Fitzpatrick emerged. A year later, William Sublette sold Fort William to the Fontenelle and Fitzpatrick partnership and agreed to leave the mountains. Thus ended the major influence of the "Ashley men” on the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade.

This same year, Jacob Astor ended his fur trade career with the selling of his holdings in the western department of the American Fur Company to Pratte, Chouteau and Company of St. Louis. The remaining portion of the American Fur Company was acquired by Ramsey Crooks. Operating on the Upper Missouri and the Great Lakes area, Crooks retained the name American Fur Company. Pratte, Chouteau and Company was now the chief supplier for what was left of the Rocky Mountain fur trade, however most journals continued to refer to them as the American Fur Company.

Two trading posts built in 1834, Fort William (Fort Laramie) by Sublette and Fort Hall by Wyeth, would have a lasting effect on travel over the Oregon Trail and the Mormon Trail. Along with Fort Bridger (built in 1843), these posts were the major supply and layover points on the Mormon, California, and Oregon trail for hundreds of thousands of weary travelers.

1835 Green River Rendezvous: Same location as 1833:

Accompanying Lucien Fontenelle with the 1835 supply train was two missionaries, Dr. Marcus Whitman and Samuel Parker. During the rendezvous, Dr. Whitman removed a metal arrowhead from Jim Bridger’s back. Bridger had been shot three years before in the Blackfeet country. The Nez Perce at the rendezvous were so receptive to having missionaries among them that Dr. Whitman returned to the East to recruit more missionaries.

Samuel Parker left a description on the plight of the mountain man.

The American Fur Company have between two and three hundred men constantly in and about the mountains engaged in trading, hunting and trapping. These all assemble at rendezvous upon the arrival of the caravan, bring in their furs and take new supplies for the coming year, of clothing ammunition and goods for trade with the Indians. But few of these men ever return to their country and friends. Most of them are constantly in debt to the company, and are unwilling to return without a fortune, and year after year pass away while they are hoping in vain for better success.

1836 Green River Rendezvous: Same location as 1833:

Narcissa Whitman and Elisa Spaulding on the way to the Oregon missions with their husbands Dr. Marcus Whitman and Henry Spalding were the first white women to attend a rendezvous and to cross South Pass on the Oregon Trail. At the conclusion of the rendezvous, the missionaries were escorted to Walla Walla by a Hudson's Bay caravan under the leadership of Thomas McKay and John McLeod. McKay's father, Alexander McKay, was with Alexander Mackenzie on his crossing to the Pacific Ocean in 1793, and a partner in the Pacific Fur Company. Alexander McKay was killed on the Tonquin at Nootka Sound.

1837 Green River Rendezvous: Same location as 1833:

Accompanying Thomas Fitzpatrick with the supply train of 1837 were Etienne Provost, Sir William Drummond Stewart, and a young artist, Alfred Jacob Miller. Stewart had brought Miller to capture on canvas the activities of the rendezvous. Stewart later took Alfred Miller to Scotland where he painted large murals based on the sketches he had made in the mountains. During the sixteen-year history of the rendezvous, neither mountain man, traveler, missionary, or visitor left a more detailed description of the wilderness experience than did Alfred Jacob Miller (Gowans).

1838 Wind River Rendezvous: Same site as 1830 Rendezvous:

The 1838 rendezvous was scheduled for the Green River Valley, but to escape trading pressure from the Hudson's Bay Company, the location was moved to the site of the 1830 rendezvous on the Wind River. This note was written with charcoal on an old storehouse door:

Come to Popoasia on Wind River and you will find plenty trade, whiskey, and white women.

According to Jerome Peltier (Mountain Man and the Fur Trade Series), Moses "Black" Harris wrote this note. Harris a frequent companion of William Sublette, has been described on several internet sites as a black man, but there is no evidence to support this other than his nickname "Black". This description of Harris was left by Alfred Jacob Miller:

This Black Harris always created a sensation at the campfire, being a capital raconteur, and having had as many perilous adventures as an man probably in the mountains. He was wiry form, made up of bone and muscle , with a face apparently composed of tan leather and whip cord, finished off with a peculiar blue-black tint, as if gunpowder had been burnt into his face.

Andrew Drips was in charge of the supply train, accompanying him was August Johann Sutter. Sutter went on to California and built Sutter's Fort where gold was discovered in 1849. Drips was also accompanied by a large group of missionaries headed for Oregon and Sir William Drummond. Stewart was making his last visit to the mountains before returning to Scotland. The 1838 rendezvous is one of the best documented rendezvous. Four of the missionary wives kept diaries.

According to Robert Newell, the company men were hard nosed in regards to business at the rendezvous. Prices were extremely high and some trappers were slipping away from the rendezvous because they could not pay the Company their debts. Credit was a thing of the past (Gowans).

1839 Green River Rendezvous: Same location as 1833:

The only account of the 1839 rendezvous is in the journal of Dr. Frederick A. Wislizenus, a German physician. Moses Harris led the train with only nine helpers...a far cry from Sublette's train to the 1830 rendezvous.

1840 Green River Rendezvous: Same location as 1833:

Andrew Drips, assisted by Jim Bridger and Henry Fraeb, directed the caravan to the 1840 Rendezvous. Leaving Westport on April 30th, 1840, it was the last fur trade caravan headed for the Rocky Mountains. With Drips was Father Pierre DeSmet and the family of Joel Walker, brother of Joseph R. Walker. Joel and Mary Walker with their five children were the first homesteaders to travel the Oregon Trail. According to Joel Walker:

About this time the Government of the United States offered emigrants six hundred and forty acres of land.

At the close of the 1840 rendezvous, an exciting chapter in American history came to an end, and another one started. The Rocky Mountain Rendezvous were over, the Oregon Trail migrations started.

Mountain men that had explored the country in search of beaver often led the wagon trains over the Oregon Trail. Two of the most famous guides were Thomas Fitzpatrick and Moses "Black" Harris. The length of the Oregon Trail is approximated at two thousand miles. It is interesting to note that wagons on the Oregon Trail traveled one- to two-miles per hour with an average of one hundred miles a week. At this rate, it took five month to reach Oregon. One estimate has one of every seventeen travelers (men, women, children) dying in route to the Oregon Country (Bailey). This gives a death rate on the Oregon Trail of over ten people per mile. The main causes of death on the Oregon Trail were disease (Cholera), crossing rivers, and accidental gun shot wounds...not from Hollywood Indians circling the wagons. One figure gives three hundred and fifty-six emigrants killed by Indians

Several factors brought an end to the Rocky Mountain fur trade era:

By 1834, men hat fashion had turned from beaver to silk hats producing a drastic effect in the price of beaver. In the early 1830's, beaver was worth almost $6/lb in Philadelphia; by 1843 the price was not even $3/lb (Virginia.edu).

In the Rocky Mountains, the relentless competition of the late 1820s and early 1830s destroyed the beaver reserves, first in the accessible areas of the central Rockies, then progressively outward from this core into the southern and northern Rockies. No other factor, even the collapse of the market after 1834, had a greater influence on the decline of the Rocky Mountain Trapping System than this blind destruction of the fur-bearing animals (Wishart).

Profit margins for the St. Louis trading firms did not justify the expense and risk of taking supplies to the rendezvous sites.

Nutria (coypu) from South America was as good as beaver for making felt hats and much cheaper to obtain.

The typical trapper left the mountains with just about what he started with...nothing. The early fur trade company owners and the St. Louis suppliers reaped any profits from the fur trade. The typical trapper never got out of debt.

There is a tendency to think that the beaver fur trade ended with the collapse of the Rocky Mountain fur trade, but fourteen years later, Hudson's Bay auctioned off five hundred thousand beaver pelts in London. Hudson’s Bay Company records show that from 1853 to 1877 the company sold some three million beaver pelts. With the end of the Mountain Man-Indian Fur Trade in the Rocky Mountains, the emphasis shifted to the Indian buffalo robe trade. In 1840 the American Fur Company sent sixty-seven thousand buffalo robes to St. Louis, and in 1848, one hundred and ten thousand robes and other skins along with twenty-five thousand buffalo tongues and great quantities of tallow (Chittenden).

The demise of the Rocky Mountain Rendezvous system signaled a new way of life for a great many Americans.

(1) The colorful buffalo robe-open sky lifestyle of the mountain man was gone.

This was the way to live, free and easy, with time all a man's own and none to say no to him. A body got so's he felt everything was kin to him, the earth and sky and buffalo and beaver and the yellow moon at night. It was better than being walled in by a house, better than breathing spoiled air and feeling caged like a varmint. - A. B. Guthrie, Jr., The Big Sky

(2) The first non-missionary wife and children traveled the Oregon Trail in 1840. Manifest Destiny had begun for the hundreds of thousands of Americans that traveled the Oregon, Mormon, and California trails.

(3) Beginning of the end for the Plains Indian Culture.

Forty-six years after the first immigrant family (Joel Walker's) traveled over the Oregon Trail, the last buffalo hunt was held in the Judith Valley, and the vast majority of free-roaming Plains Indians were confined to reservations.

The Rendezvous Site article was written by O. Ned Eddins of Afton, Wyoming. Permission is given for material from this site to be used for school research papers.