RELICDUDE07

Bronze Member

- Joined

- Oct 2, 2007

- Messages

- 2,128

- Reaction score

- 54

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- Pascagoula Ms.

- Detector(s) used

- minelab exp.

- #1

Thread Owner

James C. "Buddy" Parnell, 75, grew up hunting and fishing in the Mobile-Tensaw Delta, but his greatest catch was finding the exact location of Fort Louis, better known as Old Mobile. It didn't happen by accident. Parnell, now retired from his job as an engineering specialist at Courtaulds Fibers, worked for 14 years to document Mobile's original location.

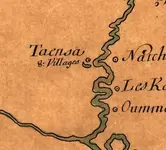

French settlers occupied Fort Louis from 1702 to 1711, when flooding caused them to move to present-day Mobile. Most historians believed Old Mobile was at 27-Mile Bluff, up on the Mobile River, but some had other theories, and archaeologists had never settled the question.

In the mid-1970s, Parnell formed the Old Mobile Research Team, consisting of friends and colleagues at Courtaulds, which is up at 27-Mile Bluff. He personally logged 2,400 hours in studying maps, conducting surveys and doing excavations - all in his spare time. He continued his search after he retired from Courtaulds in 1986. Even now, with the basic question settled, he remains passionately interested. He grumbles that the Old Mobile site isn't open to the public and that professional archaeologists working there have failed to answer key outstanding questions.

Greg Waselkov, the University of South Alabama professor now supervising the archaeological digs at Old Mobile, acknowledges that relations between him and Parnell have not always been warm. But he doesn't hesitate to give Parnell credit. "He basically showed there was not only a site, but a largely intact site, with house remains."

Parnell grew up in the Plateau section of Mobile and worked for Waterman Steamship Co. from 1938 to 1952, when he joined Courtaulds. He answered questions about his research during an interview at his Saraland home, where he lives with his wife, Mary Jean, and their 17-year-old poodle "Tonti," named after famed explorer Henri de Tonti, who is buried somewhere at Old Mobile.

What made you start looking for the Old Mobile settlement?

The whole time I was at Courtaulds, everybody up there was interested in Old Mobile, because most of it was on Courtaulds' property. And among the employees at Courtaulds were descendants of the first American settlers in that area, and there were also descendants of the French settlers. That's all they wanted to talk about, the old times, and what went on down there. What we wanted to do, beginning around 1975, was to locate the cemetery. Henri de Tonti is buried there, and some famous French clergymen. We felt like due to the significance of these people coming into the wilderness, and establishing civilization in this area, they deserved more than unmarked graves with trees growing on them. We intended to locate the cemetery, landscape it and put a fence around it. That was our goal. It turned into more than that.

What were your first steps?

We thought our work would be easy. Donald Harris of the University of Alabama had done some excavations in 1970. We had a copy of his work, so we figured to locate the cemetery all we had to do was (compare his work) with the French plats or drawings of the town. We worked from '75 to '77 with the assumption Harris was right. We'd go in the woods with transits (surveying tools) and do layouts. We were looking for any rises or sinks that could have been graves. We'd dig, but hell, we didn't find nothing.

What happened to make you expand the search?

In '77, we learned that the site had never been proven. Harris was going on the assumption that the 1902 monument marked the site. Peter Hamilton, as president of the Iberville (Historical) Society in 1902, had put that monument up there. But one of our members, Emmett Rouse, contacted all the local historians and learned that there had been three professional investigations since 1902, and none of them had proved the (Hamilton) site. So that changed the whole scope of the program. We weren't only looking for the cemetery. We had to look for the town to locate the cemetery.

What did you do next?

With the input of the Courtaulds engineering staff, we developed a systematic search plan of the supposed Old Mobile site and surrounding area. We had to account for all the natural and man-made landmarks in that area. We used known property line markers in all our surveys. We'd reference everything to that. We'd make a layout, then we'd investigate it with metal detectors. If we found nothing, we'd just move on.

This went on for years. Didn't you get discouraged?

I almost quit, because my wife was getting on me about spending all my weekends on this. Then she had second thoughts and decided she'd join me.

What was the breakthrough?

I was sitting here at the house one night. I had a 1955 aerial map (of the site), and I was studying it closely. I folded it up and held it up to the light. I saw a long straight image line. I said, 'Wait a minute.' I got a magnifying glass and looked at it again. It was a long straight line that didn't relate to any survey line, pipeline, anything of that nature. It was just there. I kept looking, and I saw two lines about 100 feet apart, at a 90-degree angle. I got all excited.

What did those lines mean?

They were image lines. And there were lots of these image lines. Some of these image lines were (French settlement) streets, turned out to be. See, when they cleared for the streets, they burned the debris, and it fertilized the ground. The vegetation grew back differently. That's what created the image lines. We began to investigate the image lines, and that's where we found our first house site.

When was that?

February 1989. I had a lot of help from Pat and Puggin (Sandra) Lomax. Pat began to notice little rises on the surface, on the terrain. He said, 'There's something right there.' We got Puggin over there with her metal detector. She went over it and got a lot of signals.

What did you find?

We found all kind of artifacts, bits and pieces of dinnerware, long clay pipe stems. We found bricks the French had made there at the site.

That must have been exciting.

It was. We celebrated. But the point is, all that labor was volunteered. It didn't cost nobody anything. We paid all our expenses.

French settlers occupied Fort Louis from 1702 to 1711, when flooding caused them to move to present-day Mobile. Most historians believed Old Mobile was at 27-Mile Bluff, up on the Mobile River, but some had other theories, and archaeologists had never settled the question.

In the mid-1970s, Parnell formed the Old Mobile Research Team, consisting of friends and colleagues at Courtaulds, which is up at 27-Mile Bluff. He personally logged 2,400 hours in studying maps, conducting surveys and doing excavations - all in his spare time. He continued his search after he retired from Courtaulds in 1986. Even now, with the basic question settled, he remains passionately interested. He grumbles that the Old Mobile site isn't open to the public and that professional archaeologists working there have failed to answer key outstanding questions.

Greg Waselkov, the University of South Alabama professor now supervising the archaeological digs at Old Mobile, acknowledges that relations between him and Parnell have not always been warm. But he doesn't hesitate to give Parnell credit. "He basically showed there was not only a site, but a largely intact site, with house remains."

Parnell grew up in the Plateau section of Mobile and worked for Waterman Steamship Co. from 1938 to 1952, when he joined Courtaulds. He answered questions about his research during an interview at his Saraland home, where he lives with his wife, Mary Jean, and their 17-year-old poodle "Tonti," named after famed explorer Henri de Tonti, who is buried somewhere at Old Mobile.

What made you start looking for the Old Mobile settlement?

The whole time I was at Courtaulds, everybody up there was interested in Old Mobile, because most of it was on Courtaulds' property. And among the employees at Courtaulds were descendants of the first American settlers in that area, and there were also descendants of the French settlers. That's all they wanted to talk about, the old times, and what went on down there. What we wanted to do, beginning around 1975, was to locate the cemetery. Henri de Tonti is buried there, and some famous French clergymen. We felt like due to the significance of these people coming into the wilderness, and establishing civilization in this area, they deserved more than unmarked graves with trees growing on them. We intended to locate the cemetery, landscape it and put a fence around it. That was our goal. It turned into more than that.

What were your first steps?

We thought our work would be easy. Donald Harris of the University of Alabama had done some excavations in 1970. We had a copy of his work, so we figured to locate the cemetery all we had to do was (compare his work) with the French plats or drawings of the town. We worked from '75 to '77 with the assumption Harris was right. We'd go in the woods with transits (surveying tools) and do layouts. We were looking for any rises or sinks that could have been graves. We'd dig, but hell, we didn't find nothing.

What happened to make you expand the search?

In '77, we learned that the site had never been proven. Harris was going on the assumption that the 1902 monument marked the site. Peter Hamilton, as president of the Iberville (Historical) Society in 1902, had put that monument up there. But one of our members, Emmett Rouse, contacted all the local historians and learned that there had been three professional investigations since 1902, and none of them had proved the (Hamilton) site. So that changed the whole scope of the program. We weren't only looking for the cemetery. We had to look for the town to locate the cemetery.

What did you do next?

With the input of the Courtaulds engineering staff, we developed a systematic search plan of the supposed Old Mobile site and surrounding area. We had to account for all the natural and man-made landmarks in that area. We used known property line markers in all our surveys. We'd reference everything to that. We'd make a layout, then we'd investigate it with metal detectors. If we found nothing, we'd just move on.

This went on for years. Didn't you get discouraged?

I almost quit, because my wife was getting on me about spending all my weekends on this. Then she had second thoughts and decided she'd join me.

What was the breakthrough?

I was sitting here at the house one night. I had a 1955 aerial map (of the site), and I was studying it closely. I folded it up and held it up to the light. I saw a long straight image line. I said, 'Wait a minute.' I got a magnifying glass and looked at it again. It was a long straight line that didn't relate to any survey line, pipeline, anything of that nature. It was just there. I kept looking, and I saw two lines about 100 feet apart, at a 90-degree angle. I got all excited.

What did those lines mean?

They were image lines. And there were lots of these image lines. Some of these image lines were (French settlement) streets, turned out to be. See, when they cleared for the streets, they burned the debris, and it fertilized the ground. The vegetation grew back differently. That's what created the image lines. We began to investigate the image lines, and that's where we found our first house site.

When was that?

February 1989. I had a lot of help from Pat and Puggin (Sandra) Lomax. Pat began to notice little rises on the surface, on the terrain. He said, 'There's something right there.' We got Puggin over there with her metal detector. She went over it and got a lot of signals.

What did you find?

We found all kind of artifacts, bits and pieces of dinnerware, long clay pipe stems. We found bricks the French had made there at the site.

That must have been exciting.

It was. We celebrated. But the point is, all that labor was volunteered. It didn't cost nobody anything. We paid all our expenses.