Hi @okstone

I didn’t notice that you had re-posted with more information, otherwise I would have replied earlier. There is a danger of us now getting into a discussion which is way outside the scope of a forum like this, so I will try to keep my answers as simple as possible.

Also (forgive me if this sounds like criticism), but my impression is that you have ‘jumped into the deep end’ by trying to understand your rock from detailed analysis of its composition without an understanding of the more fundamental aspects of geology. Nevertheless, your understanding that this could

NOT be a meteorite is 100% correct.

A few basics which might help you understand what type of rock you have. Firstly you need to understand what is know as the ‘rock cycle’, which is shown in diagrammatic form below.

View attachment 1834824

Essentially this shows that all rocks begin with magma (1), which is molten rock. That’s what the Earth was to begin with, and below the surface it still exists and is continually being created.

If that magma cools, it crystallizes and solidifies (2) and then produces igneous rocks (3). There are two types of igneous rocks. Those which form from solidification of magma below the ground which we call ‘intrusive’ or ‘plutonic’… and those which form from solidification of magma on the surface. The magma reaches the surface from rifts in the Earth’s surface or more violently via vents that we call volcanoes. These kinds of igneous rocks we call ‘extrusive’ or ‘volcanic’.

Igneous rock that have formed underground nevertheless can still be seen on the surface of Earth. They get there as a result of plate tectonics, uplifting, and other types of geological movement, or because they have become exposed by erosion. Although igneous rocks are generally hard and resistant, they do ultimately erode and weather (4), producing debris as smaller fragments. If that debris is carried by water, the fragments become progressively smaller and more rounded. Ultimately they will become mud, clay and silt by further erosion and aqueous alteration.

They then accumulate as ‘sediments’ (5) which ae usually water-carried (rain or rivers) and when they become deposited in layers they can become consolidated into sedimentary rocks (6). That happens as a result of drying out, crystallisation of other minerals from groundwater, or as a result of pressure from what gets deposited on top of them.

The cycle continues if those sedimentary rocks become buried and there is enough pressure to create sufficient heat for metamorphism (7), leading to metamorphic rocks (8). If they completely melt (9), they turn back into magma and the cycle starts again.

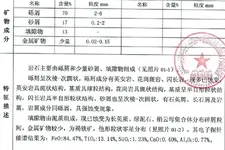

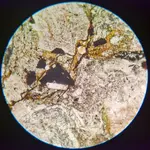

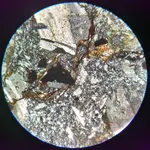

What the analysis for your rock says is that it’s a

sedimentary rock. There are no known sedimentary meteorites. They’re also saying it’s a conglomerate, which is a sedimentary rock composed of small grains of debris from other rocks that have become cemented together. In this case the grains are largely gravel and sand, including at least some volcanic/igneous material, but the rock itself is still sedimentary. You’re effectively at stage (6) in the rock cycle above. The cementing material is said to be argillaceous, which essentially means that it is composed of mud or clay formed by aqueous alteration of other minerals derived from rock fragments.

In short your rock is typical for a mixture of eroded rock fragments which have been water-carried from elsewhere and deposited together with mud as a mixed sediment in an environment where the groundwater was rich in iron… and then solidified as a conglomerate.

I hope that helps a bit.