Re: $3B WWII Shipwreck Located in Boston Harbor's Back Yard

arctic said:

I stress what I said previously: it reeks of scam.

Platinum plunder or fool's gold?

Greg Brooks, posing alongside the salvage ship Sea Hunter in Boston Harbor on Feb. 1, claims his Portland, Maine, company Sub Sea Research has found billions of dollars in platinum ingots and other treasures inside the wreck of the Port Nicholson.

The Associated Press/Winslow Townson

By Doug Fraser

dfraser@capecodonline.com

February 26, 2012

An investor in what Greg Brooks insists is the greatest shipwreck treasure ever found would have to believe that up to $5 billion in platinum, gold and diamonds has been hiding in plain sight for 67 years and no one had any interest in recovering it.

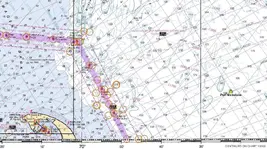

In a highly competitive business where the truth is too often a movable target, Brooks claims his company, Sub Sea Research of Portland, Maine, has found billions of dollars in platinum inside the wreck of the World War II British freighter Port Nicholson, 50 miles northeast of Provincetown.

The 481-foot freighter was sunk on June 16, 1942, by a German U-boat as it was traveling in a convoy from England to New York. The ship took six hours to sink. Six crewmen died, but there were 85 survivors, including the captain. Brooks and Edward Michaud, the senior researcher for Sub Sea, say it contains billions of dollars in platinum ingots and other treasures and that the British, Soviet and American governments knew about the treasure.

Despite that the Nicholson wreck is located in relatively shallow water at 600 to 800 feet and that it is just a day trip from shore, Sub Sea has struggled for nearly three years to recover any treasure and has yet to penetrate the cargo hold where they believe it is stored. The company burned through the $6 million it initially raised from investors for the Nicholson project. Brooks is pushing hard now to get $800,000 more to retrieve at least one platinum bar, which he hopes will encourage more investors. He is hoping to be back on the site of the shipwreck by the end of this month or sometime in March.

But critics say Brooks' track record gives him little credibility and there's no proof he's found the vessel or that there is anything but auto parts and military supplies on board.

Take a number, Brooks says to his many skeptics, you'll soon be eating crow. "Once I have (the platinum ingots) on deck, all the naysayers, everybody, will sing a different tune," he said in a recent interview.

n n

Brooks, a former swimming pool installer turned Maine-based treasure hunter, claims that the bulk of the platinum gold, and diamonds lie in the Nicholson's No. 2 cargo hold, and as many as 30 boxes containing ingots are strewn across the ocean bottom surrounding the wreck. Divers using specialized gas mixes and equipment have worked other wrecks at even greater depths, experts say, and they wonder why, if the treasure is so close at hand, it has been so long with not even a single bar of platinum being recovered.

For example, in 1942, the HMS Edinburgh, carrying $68 million in gold bullion was torpedoed and sunk off the Soviet coast in 800 feet of water. Salvagers working for the British started looking for the wreck 10 years later. Work was interrupted by the Cold War, but in 1981, thanks to an agreement between Russia and Great Britain, divers cut through the vessel's armor plating and within six months of discovering the wreck they had nearly all the gold on deck.

Brooks blames bad weather, strong currents and equipment failure for delays in getting the Nicholson treasure.

The company's remote operated vehicle is too small for the job. It was built for inspection work, not salvage operations, Brooks said. It lacked the power to handle currents, to clear the debris blocking access to the cargo hold or to lift the heavy crates outside the ship that purportedly contain platinum ingots. And Sub Sea's mother ship, the 221-foot Sea Hunter, doesn't have the dynamic stabilization system incorporating computer-assisted navigation and directional thrusters that are standard in oil exploration and other research vessels to keep them in a stable position.

But Brooks faces a more fundamental challenge: proving to investors and others that the ship has treasure on board.

He declined the Times' request to provide documentation to back up his claims on the platinum. He did show a CBS news reporter a heavily redacted copy of what he said was a ship's manifest that mentioned the Port Nicholson and seemed to indicate that 1.7 million ounces of platinum were on board. Sub Sea has yet to produce a document Michaud said he discovered in U.S. Treasury archives that, he says, proves the U.S. government was expecting a shipment of platinum on the Nicholson.

Brooks, however, has released several Internet videos to make his case for the Port Nicholson.

The videos show a brightly colored sonar image of a submerged freighter lying on its side as well as close-up shots from a ROV that reveal lettering on the bow Brooks says spell out "Nicholson." He has superimposed lettering on the images to help viewers discern each letter through the hull's heavy encrustation of debris and marine growth.

Video footage also shows crates scattered along the ocean bottom around the ship that Brooks claims match ammunition crates the Soviets used to ship gold bullion on the Edinburgh. Using a weight gauge attached to the robotic arm of the ROV, the crew estimated the weight of most of the crates at more than 200 pounds. That's heavy enough, Brooks suggested, to be platinum.

"There's no doubt that on the next trip he (Brooks) is going to come back with something," said Michaud a Framingham resident. "These types of operations take an awful long time."

n n

Michaud's confidence does not assuage critics who claim that Brooks, like many treasure hunters, inflates claims to attract investors but has produced relatively little. And in at least three prominent cases, Brooks and Michaud didn't get their basic research right.

"I'm skeptical as a standard point of view about anything having to do with treasure hunting," said Jim Miller, Florida's state archaeologist for more than 20 years. "It's an area where there are lots of opportunities for being loose with the truth."

As state archaeologist, Miller kept tabs on a prior Sub Sea project in 2002 when Brooks claimed to have found the wreck of the Notre Dame de la Deliverance, a 166-foot French vessel working under contract with Spain, off Florida. Brooks said it had $2 billion to $4 billion in gold on board.

Now retired, Miller helped write Florida's permitting system that governs maritime salvagers when their wreck site lies in both state and federal waters. Although the permits require that the applicant submit primary evidence, Miller does not recall that Brooks submitted any. The federal government denied him salvage rights within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, but Sub Sea was able to secure exclusive rights to the shipwreck in federal court when Brooks presented a piece of lead sheathing he said was from the bottom of the vessel.

"That's like finding a piece of tire on the side of the road and claiming you know what kind of truck it came from," Miller said.

His own investigation into the Deliverance failed to turn up any documentary evidence that any such ship by that name was ever anywhere near where Brooks was looking. "Could be there was a Deliverance somewhere, but I found no record of one being in that area," Miller said.

After making huge claims and generating a lot of publicity, Brooks' company abandoned the search for the Deliverance with little fanfare a few years later, said John Hallas, the chief of maritime cultural resources for the Florida sanctuary.

In 1995, Michaud claimed to have uncovered documents showing that a German sub had been sunk in only 41 feet of water four miles off Monomoy Island. As president of Trident Research & Recovery of Framingham, he entered into a joint venture with Sub Sea to find the vessel.

Michaud's story changed, however, as time went on. First, he said, a Navy plane had bombed the sub. Then, he said it had been sunk by a depth charge from a Navy blimp in 60 feet of water. Over the years, the original sub metamorphosed into a top-secret experimental vessel he described as "Hitler's Escape Boat" and code-named the Black Knight.

According to news reports at the time, the U.S. Navy said no sub had ever been sunk in that area, and the German government attested that the last broadcast of the original sub Michaud claims to have found, U-1226, came from the mid-Atlantic the day before it disappeared. Michaud claimed he had found the sub on sonar, but despite repeated attempts, it was never located.

Michaud also claimed he had found evidence that a Nazi sub, U-233, had sunk in Casco Bay, Maine. That was never validated, either.

"It is not in Casco Bay," said Harry Cooper, president of Sharkhunters, a Florida website on U-boat history with 7,600 members, including former U-2 captains and crew. German and U.S. naval records show the sub sank 1,000 miles to the east of where Sub Sea claimed it was located, Cooper said. And there was no credence to Michaud's story of a sunken German sub off Chatham, either, he said.

n n

Michaud replies to such criticism by saying, "I know what I do and the research I have."

He insists he has hundreds of pages of documents on the Port Nicholson that show the ship was carrying platinum loaded in Murmansk as a transfer from the Soviet government to the U.S. for a lend-lease payment. He would not show any documents to the Times, however.

Skeptics argue that Sub Sea's track record should be enough to warn off potential investors.

"Based on the facts, he's a non-producer," said veteran treasure hunter Burt Webber in a phone interview from the Dominican Republic where he has spent the past 40 years researching and finding Spanish galleons and other historic shipwrecks in partnership with the Dominican government. "What I say I found, I can document. The ones I saw pursued (by Brooks), these were all bedtime stories," said Webber, who admitted he knew little about the Port Nicholson or the treasure it supposedly contains.

The only treasure that most salvagers find is in the investor's pockets, said Filipe Castro, an associate professor of marine archaeology at Texas A&M University. He is highly critical of the industry and those who put money into it hoping to strike it rich.

"I think that treasure hunters look for a particular type of investor. Not the sharpest knife in the drawer, if you know what I mean," Castro said. "I don't have a lot of sympathy for dumb, infantile, greedy, rich people. If they lose their money and come back for more, what are the treasure hunters going to do?"

Paul Lawton, an underwater search and survey consultant and attorney from Brockton, says he's been following Brooks' endeavors for more than 20 years. Based on news articles and archived pages from Sub Sea websites, Lawton estimates that investors have been promised treasure totaling more than $11 billion in various Sub Sea projects, but have received little or nothing for their money.

"This is just another one of many bogus treasure salvage tales they have spun to bilk hapless investors, as they have done nearly a dozen other times over the past two decades," Paul Lawton wrote to the Times about the Port Nicholson.

n n

Brooks insists the treasure on board the Port Nicholson is real, and that he will prevail over his critics.

He and Michaud say the treasure-hunting business is filled with risk — for those who venture far from shore to retrieve treasure and for investors who hope for a spectacular payoff but more often than not end up with nothing, or a souvenir. "Most of the industry is like that," Michaud said. "A lot of people get bilked. Even the good companies are risky."

Brooks declined a request by the Times to turn over evidence of any returns. Instead, he said that investors never really lost money in any of his ventures because their investments were rolled over into the next project. "Our investors are all still in it from day one. When we complete the project, they will be paid off handsomely," he said.

Even if he does find the treasure he seeks, he may face significant legal hurdles.

"Under the War Risk Insurance scheme, merchant vessels lost during the two World Wars became the property of the U.K. government if insurance was paid out," the British Department for Transport wrote in an email response to questions from the Times.

"The U.K. is therefore the owner of the wreck of the SS Port Nicholson. To protect our interest in the vessel and its contents, we are currently party to court proceedings in the U.S. and are considering our next steps."

![Lading document-portion[2].webp](/data/attachments/603/603347-86e8339447f50891230ea81aaff8738f.jpg?hash=CetdWuDkiL)