- Feb 3, 2009

- 38,855

- 146,021

- 🥇 Banner finds

- 1

- Detector(s) used

- Deus, Deus 2, Minelab 3030, E-Trac,

- Primary Interest:

- Relic Hunting

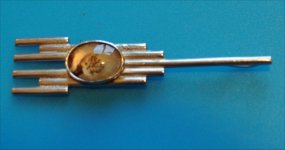

Trying to get the date and the maker of this watch chain, hoping somebody can provide some insight please.

I think it's from Birmingham

Not sure if that A is from 1888 or 1900 for the date code

.

Can't match the maker up from the records either. J.W.B.Ld

Watch chain 44 grams, 22 inches long.

I think it's from Birmingham

Not sure if that A is from 1888 or 1900 for the date code

.

Can't match the maker up from the records either. J.W.B.Ld

Birmingham Hallmarks 4 - Encyclopedia of Silver Marks, Hallmarks & Makers' Marks

Birmingham Hallmarks, Makers' Marks & Date Letters on Antique Sterling - Online Encyclopedia of Silver Marks, Hallmarks & Makers' Marks

www.925-1000.com

Watch chain 44 grams, 22 inches long.