TripleCreek

Jr. Member

- Joined

- Jan 27, 2009

- Messages

- 71

- Reaction score

- 2

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- Mid Maryland

- Detector(s) used

- Tesoro- DeLeon

It has occurred to me that when collecting artifacts we hardly ever see the organic component (wood, bone, leather, pitch, glue etc.) that were part of the function of the ordinal stone tool.

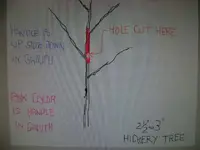

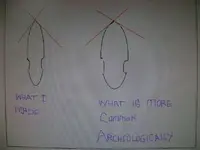

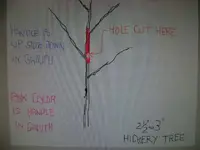

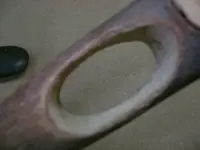

In describing a halfting principle in another tread, I described what was needed to half a celt. I thought it would be good to do a pictorial thread to show an example of what I described. Celts are the most modern of the stone ax development. Full grooved axes, were the earliest, and half grooved were the next development, and then the halfting changed completely, to a simple compression fit, in a hole in the handle for Celts. No adhesives, glue, or binding was used in a halfting a celt. As "illustrated" a hickory tree made a good choice for a handle, and it was most often cut, upside down, with a tree limb knot used, to streathen the weak area above the celt. The pictures of the celt handle, are of a reproduction done with modern tools, but historically accurate. The celt was also reproduce with modern tools but finished with historically accurate method of grinding, and polishing.

The full grooved axe is a reproduction done, historically acturate, with no modern tools used. I did the full grooved ax as an experiment to check the efficiency of the stone tool. It took me about 25 hours. of pecking and grinding to finish this ax. I eventually cut down two trees with this ax. I had my son count the strokes required to cut these trees. The first tree was a walnut, about 6" in diameter, and it took 180 chops to cut through this tree. ( I cut the walnut tree by mistake, I thought it was a black locus tree, but did not realize I had cut the wrong tree till it fell) I wanted a black locus tree to use as a bow blank, and the leaves got mixed up at the top and; oops, it happens. The second tree was about an 8" in diameter, and was a black locus tree. At about half way through (the locus was a much harder tree wood) at about 150 chops, I got to the heartwood (the dark wood in the center of the tree) and kept hitting hard, and one hit spalled off a beautiful flake that traveled all the way up the side of the ax. (see picture) I should have stopped and resharpened the ax right then, but I continued and the bit of the ax started immediately to disintegrate. It took another 222 chops to fell the tree with a continually less efficient bit on the ax. Obviously, I need to reevaluate what I am doing since I can not imagine primitive peoples spending 25 hours making a tool that only cuts down two small trees. I believe that I did not have a steep and rounded enough edge going to my bit, that made it more susceptible, to spalling a flake off. Also, I think an ancient person would have "babied" that tool a lot more then I did, especially when chopping into that very hard heartwood on that black locus tree.

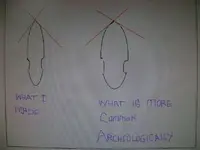

(Sorry about the poor quality drawings, I could'nt figure how to post "paint" drawings, so I had to take a picture of the computer screen)

3creeks

In describing a halfting principle in another tread, I described what was needed to half a celt. I thought it would be good to do a pictorial thread to show an example of what I described. Celts are the most modern of the stone ax development. Full grooved axes, were the earliest, and half grooved were the next development, and then the halfting changed completely, to a simple compression fit, in a hole in the handle for Celts. No adhesives, glue, or binding was used in a halfting a celt. As "illustrated" a hickory tree made a good choice for a handle, and it was most often cut, upside down, with a tree limb knot used, to streathen the weak area above the celt. The pictures of the celt handle, are of a reproduction done with modern tools, but historically accurate. The celt was also reproduce with modern tools but finished with historically accurate method of grinding, and polishing.

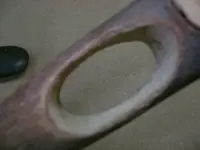

The full grooved axe is a reproduction done, historically acturate, with no modern tools used. I did the full grooved ax as an experiment to check the efficiency of the stone tool. It took me about 25 hours. of pecking and grinding to finish this ax. I eventually cut down two trees with this ax. I had my son count the strokes required to cut these trees. The first tree was a walnut, about 6" in diameter, and it took 180 chops to cut through this tree. ( I cut the walnut tree by mistake, I thought it was a black locus tree, but did not realize I had cut the wrong tree till it fell) I wanted a black locus tree to use as a bow blank, and the leaves got mixed up at the top and; oops, it happens. The second tree was about an 8" in diameter, and was a black locus tree. At about half way through (the locus was a much harder tree wood) at about 150 chops, I got to the heartwood (the dark wood in the center of the tree) and kept hitting hard, and one hit spalled off a beautiful flake that traveled all the way up the side of the ax. (see picture) I should have stopped and resharpened the ax right then, but I continued and the bit of the ax started immediately to disintegrate. It took another 222 chops to fell the tree with a continually less efficient bit on the ax. Obviously, I need to reevaluate what I am doing since I can not imagine primitive peoples spending 25 hours making a tool that only cuts down two small trees. I believe that I did not have a steep and rounded enough edge going to my bit, that made it more susceptible, to spalling a flake off. Also, I think an ancient person would have "babied" that tool a lot more then I did, especially when chopping into that very hard heartwood on that black locus tree.

(Sorry about the poor quality drawings, I could'nt figure how to post "paint" drawings, so I had to take a picture of the computer screen)

3creeks

Upvote

0

Ive never attempted to make a ax or a celt! How long does the grinding process normally take?

Ive never attempted to make a ax or a celt! How long does the grinding process normally take?