I'm not a knapper so are you saying it's taken five years for you to reach this level ?

No, these are flaking results from flaking processes that were not known to modern science. I found evidence that such processes existed, via archaeological evidence, historical evidence, and ethnographic evidence. I had an idea about the tools. But, I did not know how it worked. It took five years to figure out how to use the tools, to make the processes work.

The problem is that our modern flintknapping theories were mostly put together by European academics, who had almost no knowledge of New World flintknapping. The original flintknapping model was based upon hammerstone percussion. By the end of the 18th century, people in Europe came to realize that there were clear associations of what they called "pebble hammers", and ancient chipped stone tool production. So, a great deal of early experimentation, primarily during the 19th century, was focused on the use of "pebble hammers" - what we would call hammerstones.

During that time, many in Europe speculated that the red man of the American continents still possessed stone tool manufacture technologies, since the Americas were discovered to be in the Stone Age, in 1492, and the red men were known to still be making stone tools, in some areas, during the 19th century. The publication of Catlin's two man indirect percussion account was printed in 1867, and widely cited throughout Europe. Unfortunately, it was poorly understood, and Catlin died just a few years after publication.

Then, a European researcher published a work, probably ten years after Catlin, which likened ancient stone tool production, to the work of the modern-day British gunflint knappers. Once again, the focus shifted back from indirect percussion, to direct percussion. But, by the end of the 19th century, it was determined that there were certain limiting factors in hammerstone direct percussion. And, these limiting factors made it more and more difficult to do a good job, as the point became thinner, and flatter. As a result, European academics adopted the use of the "pressure flaker", into their paradigm.

Still, between these two flaking processes, there appeared to be a missing intermediate flaking, larger than pressure flakes, but finer than percussion flakes. This missing flaking eluded researchers. Meanwhile, the information from the Americas seemed to be all but lost, since the work had previously been in the hands of specialists. And, most work had been phased out by the early 19th century. So, between the 1920's and 1930's researchers began to give up on the hammerstone plus pressure flaker model.

Then, during the 1930's, an English researcher by the name of Barnes carried out a series of baton experiments, in his laboratory, in London. He struck a block of chert with a wooden baton, and antler baton, an ivory hammer, and a piece of brass. The flakes that most resembled the ancient flakes, were the antler baton flakes. This spawned a new theory - the intermediate flakes could have been made via an antler baton. This theory was further developed by Louis Leakey in the 1940's, then by Francois Bordes in the 1950's, and then brought to American television via the work of Don Crabtree, in the 1960's.

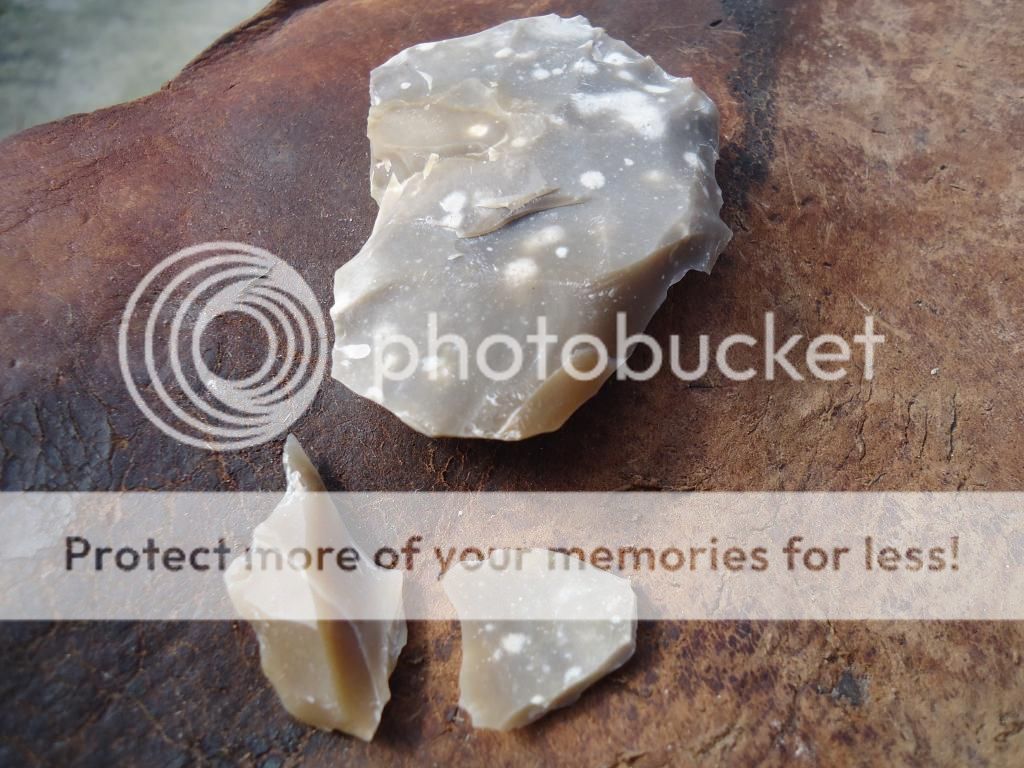

In 2010, I was doing research on a very obscure form of Lacandon flintknapping, that involves holding a small antler punch between two fingers, next to a piece of stone, and striking with a striker in the other hand. While trying to find further information, I stumbled upon a small tool known as "antler drift", which is a flintknapping tool common to North America, and comparable to a small cylinder of antler, about one centimeter thick, and one and a half to two and a half inches long. "Grim Reaper" posted some here, sometime back.

The peculiar thing about the antler drift cylinders is that archaeologists suspected that they were used in the indirect percussion flaking of chert, for about one century, going back to the early 1900's. But, no one ever knew how such work was carried out.

My guess was that there should have been some carryover, somewhere, into the historical era. And, from that information I hoped to put together how the tool was once used. After spending several years sifting through several thousand sources of material, what I discovered is that there was a great deal of evidence of various forms of sophisticated indirect percussion being used, among Native American flintknappers.

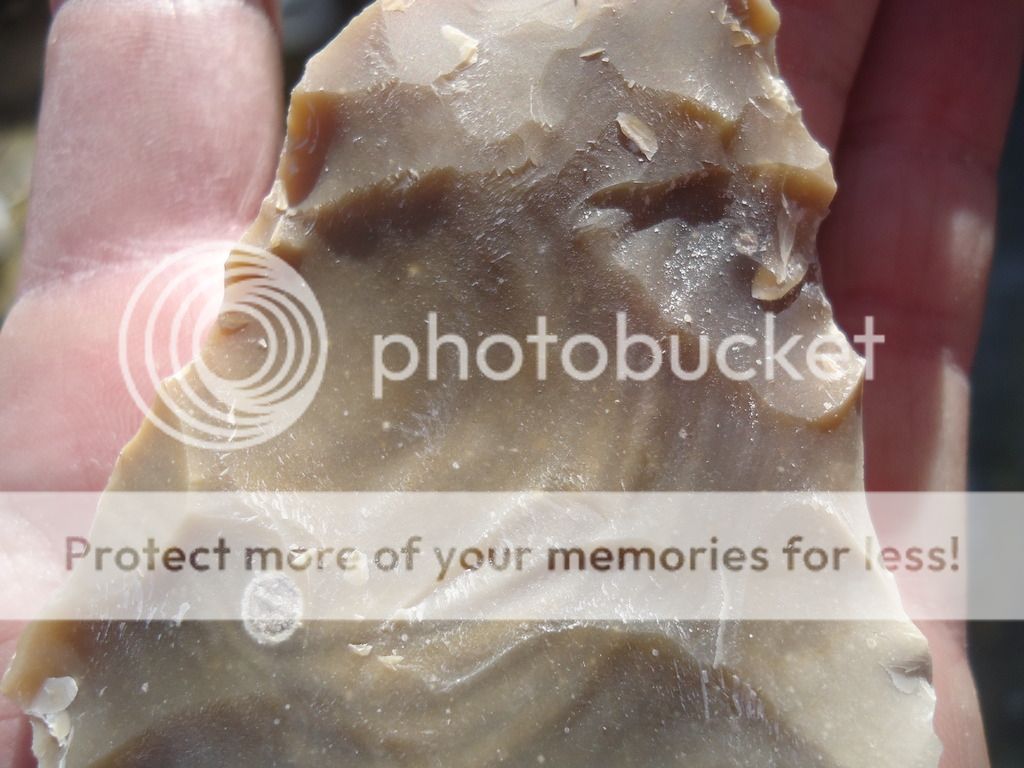

As a result of all of this evidence, I broadened all of my experiments, to see whether something would lead to an answer regarding antler drift flaking cylinders. The irony is that I appear to have discovered the full blown paleoindian outrepasse flaking technology, before I discovered a possible answer to the antler drift question. Meanwhile, by 2011, I pretty much gave up on the antler baton theory, for lack of critical evidence.

Here is the crux of the problem. The European academics who came up with theories, and paradigms, that are still being taught today did not anticipate the degree to which prehistoric American flintknappers blended their technologies. In other words, the Europeans gave a crisp, clear cut understanding of "direct percussion", "pressure flaking", etc. Each tool, and tool process, produced (at least in theory) a straightforward, and definable, effect. It is all linear thinking.

The problem with trying to apply this thinking to more recent historical evidence, ethnographic evidence, etc, is that no one has ever PROVEN that ancient knappers took the same approach. To the contrary, even accounts from the 19th century show that Native American flintknappers were using blends of technologies. And, this is something that is never understood by modern flintknappers. The secret is that by creating blends of flaking technologies, the flintknapper can create secondary flaking forces, that cannot be directly created. This is the epiphany that I had in January of 2015. And, that is why I was immediately able to produce full length Clovis style outrepasse flakes, with a common deer tine, just fifteen minutes after having the epiphany. Now, how the First Americans understood all of this, I have no earthly clue... I looked at the evidence everyday, for five years, before I understood what was going on.

Anyway, very few people have interest in "flakers". They are more interested in "finished points". But, if people show their flakers, I may be able to show a possible, or even probable, use of the flaker.