You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

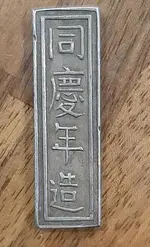

Need Help with ID of an Asian bar

- Thread starter StilloesEmporium

- Start date

- Joined

- Dec 23, 2019

- Messages

- 6,330

- Reaction score

- 20,210

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- Surrey, UK

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

Welcome to Tnet

For you to ask if it's fake or reproduction, it suggests that you have some idea of what an authentic one would be. It really helps if you tell us what you already know!

It's what's known as a silver "Annan bar" (also quoted as "Annam"), used as currency (mainly in trade) and also for payment of taxes in what was once part of China as the "Annan Province" or "Tang Protectorate" and then ultimately Vietnam.

The characters will give the denomination/value and reign era as a date span, They also sometimes have an indication of a specific purpose, such as payment of tobacco tax. That style would typically date from the first half of the 1800s but we need a Chinese speaker to translate for us (both sides). Calling Yang Hao?

I don't know if it's genuine or not but, if it is, it would likely be a rather late example. Reproductions are not uncommon.

For you to ask if it's fake or reproduction, it suggests that you have some idea of what an authentic one would be. It really helps if you tell us what you already know!

It's what's known as a silver "Annan bar" (also quoted as "Annam"), used as currency (mainly in trade) and also for payment of taxes in what was once part of China as the "Annan Province" or "Tang Protectorate" and then ultimately Vietnam.

The characters will give the denomination/value and reign era as a date span, They also sometimes have an indication of a specific purpose, such as payment of tobacco tax. That style would typically date from the first half of the 1800s but we need a Chinese speaker to translate for us (both sides). Calling Yang Hao?

I don't know if it's genuine or not but, if it is, it would likely be a rather late example. Reproductions are not uncommon.

Last edited:

Upvote

0

Bottom two characters appear similar to yours.

https://www.ebay.ca/sch/i.html?_nkw=annam+bar+lang

I have no idea of authenticity.

Don....

https://www.ebay.ca/sch/i.html?_nkw=annam+bar+lang

I have no idea of authenticity.

Don....

As an eBay Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Upvote

0

- Joined

- Dec 23, 2019

- Messages

- 6,330

- Reaction score

- 20,210

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- Surrey, UK

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

The similarity of some characters often doesn't help much since they often translate as "made in the reign of..." or something similar and they can also be the value/denomination common across many examples. We need an exact match to all the characters or a precise translation. I've dropped a PM to our esteemed member Yang Hao to ask if he can help.

Upvote

0

- Joined

- Dec 23, 2019

- Messages

- 6,330

- Reaction score

- 20,210

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- Surrey, UK

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

PS: a translation may or may not tell us whether it's a reproduction unless it "claims" to be much earlier than its style suggests.

Upvote

0

islamoradamark

Silver Member

- Joined

- Aug 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,630

- Reaction score

- 3,993

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

Welcome to Treasure net like the bar

Upvote

0

Yang Hao

Sr. Member

It looks to be from Vietnam between 1885 to 1889 (if authentic) the 同慶 pinyin is tongqing (Đồng Kh?nh) which means collective celebration in Vietnamese. It's the name of the ninth emperor of the Nguyễn Dynasty of Vietnam. The Wiki page link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Đồng_Khánh

The characters on the item: (this is just my quick translation of each character)

同慶年造:同慶 Đồng Kh?nh emperor, 年 year, 造 created/made.

內帑銀五錢 (內帑treasury 銀silver 五5 錢money )

Hope this helps. Happy treasure hunting.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Đồng_Khánh

The characters on the item: (this is just my quick translation of each character)

同慶年造:同慶 Đồng Kh?nh emperor, 年 year, 造 created/made.

內帑銀五錢 (內帑treasury 銀silver 五5 錢money )

Hope this helps. Happy treasure hunting.

Upvote

0

- Joined

- Dec 23, 2019

- Messages

- 6,330

- Reaction score

- 20,210

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- Surrey, UK

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

It looks to be from Vietnam between 1885 to 1889 (if authentic) the 同慶 pinyin is tongqing (Đồng Kh?nh) which means collective celebration in Vietnamese. It's the name of the ninth emperor of the Nguyễn Dynasty of Vietnam. The Wiki page link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Đồng_Khánh

The characters on the item: (this is just my quick translation of each character)

同慶年造:同慶 Đồng Kh?nh emperor, 年 year, 造 created/made.

內帑銀五錢 (內帑treasury 銀silver 五5 錢money )

Hope this helps. Happy treasure hunting.

Fantastic. Thank you very much Yang Hao.

So, the claimed dating is consistent with a late 1800s styling and I would say that ups the chances of it being authentic.

Upvote

0

xaos

Bronze Member

- Joined

- Jul 3, 2018

- Messages

- 1,062

- Reaction score

- 2,302

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

It does not look like silver....and for the age, way too perfect...

Looks like a local pawn shop can tell you if its silver or not...

Looks like about 38 grams is the key weight...

https://www.coinshome.net/en/coin_d...hinese_province)-ZmsKbzbi_mkAAAFNHzNWb1Dy.htm

Looks like a local pawn shop can tell you if its silver or not...

Looks like about 38 grams is the key weight...

https://www.coinshome.net/en/coin_d...hinese_province)-ZmsKbzbi_mkAAAFNHzNWb1Dy.htm

Last edited:

Upvote

0

- Joined

- Dec 23, 2019

- Messages

- 6,330

- Reaction score

- 20,210

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- Surrey, UK

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

It does not look like silver....and for the age, way too perfect...

Looks like a local pawn shop can tell you if its silver or not...

Looks like about 38 grams is the key weight...

https://www.coinshome.net/en/coin_d...hinese_province)-ZmsKbzbi_mkAAAFNHzNWb1Dy.htm

I don’t know whether this is genuine or not, and a specialist catalogue is really needed to see if it matches correctly to known examples. As I said, replicas are not uncommon.

However, I don’t agree with your assessment. I don’t believe it’s possible to say whether or not it is in fact silver from a photograph (although a replica could of course also be made from silver).

The website you linked to shows units of “one lang” with weights around 38g but the weight of these pieces varied according to their denomination (and also a little as a result of changing silver prices and/or silver purity because they were “bullion currency”).

Yang Hao’s translation tells us this example is a unit of “5”, so it won’t necessarily be anywhere near 38g. It gets complicated because these bars (also sometimes called “trays”) were linked to Chinese currencies, which in turn were linked to the unit of weight known as the “tael” which was approximately 40g… but with actual currency values fluctuating for the reasons I gave above. My guess is that it was intended to be valued at “5 tien”, the tien being the prevailing monetary unit in imperial Vietnam during the 19th Century, but that’s not the only possibility. One tien could be anywhere between 3 and 4 grams of silver. An actual weight of the piece would be helpful.

Also, the examples in your link are generally older pieces than this one. The workmanship varies enormously according to the merchant bank that produced them, and also progressively improved with time through the 1800s, which is why I said this would have to be a late example, so I was encouraged by Yang Hao’s translation that it has an imperial date span between 1885-1889.

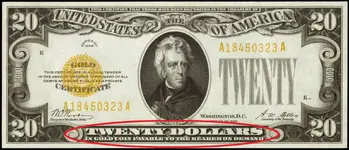

It’s not “way too perfect” for its age to rule out it being genuine. Even by the mid-1800s, workmanship standards could be pretty high, as evidenced by this 5 tien piece from between 1820-1841 (and later pieces can be better still):

Last edited:

Upvote

0

Yang Hao

Sr. Member

I don?t know whether this is genuine or not, and a specialist catalogue is really needed to see if it matches correctly to known examples. As I said, replicas are not uncommon.

However, I don?t agree with your assessment. I don?t believe it?s possible to say whether or not it is in fact silver from a photograph (although a replica could of course also be made from silver).

The website you linked to shows units of ?one lang? with weights around 38g but the weight of these pieces varied according to their denomination (and also a little as a result of changing silver prices and/or silver purity because they were ?bullion currency?).

Yang Hao?s translation tells us this example is a unit of ?5?, so it won?t necessarily be anywhere near 38g. It gets complicated because these bars (also sometimes called ?trays?) were linked to Chinese currencies, which in turn were linked to the unit of weight known as the ?tael? which was approximately 40g? but with actual currency values fluctuating for the reasons I gave above. My guess is that it was intended to be valued at ?5 tien?, the tien being the prevailing monetary unit in imperial Vietnam during the 19th Century, but that?s not the only possibility. One tien could be anywhere between 3 and 4 grams of silver. An actual weight of the piece would be helpful.

Also, the examples in your link are generally older pieces than this one. The workmanship varies enormously according to the merchant bank that produced them, and also progressively improved with time through the 1800s, which is why I said this would have to be a late example, so I was encouraged by Yang Hao?s translation that it has an imperial date span between 1885-1889.

It?s not ?way too perfect? for its age to rule out it being genuine. Even by the mid-1800s, workmanship standards could be pretty high, as evidenced by this 5 tien piece from between 1820-1841 (and later pieces can be better still):

View attachment 1941621

Thanks for pointing out my error Red Coat (I was busy at that time grading term papers). It should translate more like 5 units of currency of that time. Going by Chinese 银 yin 銀 it does mean silver but it can also mean relating to money or currency. For example 銀行 yinhang means "bank" in Chinese. The 行 hang means business and distribute (silver distribution/silver exchange). In the past banks did deal with gold and silver (and still do but not as much). Maybe, the bar is a "metal note currency" equal to 5 units of silver. Similar to USA paper currency in 1928 that said "In gold coin payable to the bearer on demand". If going by that theory, it's a metal bar being backed by silver (instead of gold like the US did in the past)... Happy treasure hunting.

Last edited:

Upvote

0

Similar threads

- Replies

- 10

- Views

- 679

- Replies

- 7

- Views

- 254

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)