Organized Crime in 19th-Century Central New York

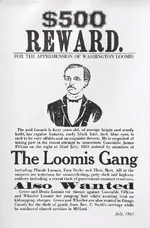

The center of Sangerfield lies at the crossroads of Route 20 and Route 12, about 42 miles west of Sharon Springs. The region was once a marshy area, part of what the Oneida Indians called Skawanis, the Great Swamp. It became known to non-Indians as Nine Mile Swamp. One family who lived on a hill in the swamp, some four miles to the southwest of the crossroads, knew the countryside’s firm ground and its dangerous places and used this knowledge to their advantage in hiding stolen goods. Known as the Loomis Gang, this crime syndicate – the largest in the nation in the mid-19th century – helped themselves to other people’s property in central New York.

George Washington Loomis, raised in Connecticut and having lived in Vermont before being chased by a posse across the border into New York for stealing horses, joined his sister Clarissa in Sangerfield in 1802. It was a time of population and economic growth on the western frontier. The Oneida Indians had been swindled out of most of their landholdings, allowing new development, and the Cherry Valley Turnpike was being expanded westward (see our earlier blog). The Loomis family had been a reputable aristocratic family in New England for generations, but George and his wife Rhoda Marie Mallet Loomis had a criminal bent and raised their ten children on their farmstead accordingly. Rhoda, whose father, an officer in the French Revolutionary prosecuted for embezzlement, reportedly informed her children, “You may steal, but if you are caught, you shall be whipped.”

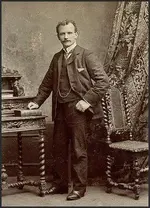

George Washington Loomis, Jr., known as Wash, the second of six sons, became the ring leader under his parents’ tutelage. By all accounts he was sophisticated and well-dressed and had a way with words and a magnetic personality. To sharpen his criminal wits, Rhoda even arranged that Wash study in a law office. The third son, Grove, demonstrated great aptitude for his father’s specialty, stealing horses. The family recruited others besides their ten children to join in their criminal activities. Another one of Rhoda’s reported admonitions to her children and their trusted friends on leaving her home was, “Now don’t come back without stealing something, if it’s nothing but a jackknife.”

The Loomis Gang specialized in horse thievery and livestock rustling, but burgled homes as well and were even known to rob clotheslines. George, Sr., and his brothers Walter and Willard also became experts at counterfeiting money. For protection the Loomis Gang treated neighbors well and paid off local authorities. Those who opposed them were likely to lose their barns in fires. But gang members consistently had alibis. They also had funds to hire top lawyers to defend gang members or associates. With the growth of their criminal empire, their influence reportedly extended to state officials in Albany.

In 1848, with growing anger over the Loomis Gang’s continuing criminal reign, an armed party of locals raided the Loomis farm and found numerous stolen goods that had not yet been resold or moved to caches in the swamp. Through legal maneuvering gang members managed to avoid conviction. But, given the pressure and pending charges, Wash decided to leave town in early 1849, and charges against him were dropped in both Oneida and Madison Counties. It was the time of the California Gold Rush, and he headed westward to seek another kind of fortune. The family’s criminal activities slowed down for a time. Wash, with little success as a gold prospector, returned to central New York in late 1850 and picked up where he had left off. His father George, Sr., died the next year, but the family and far-flung associates continued to thrive. By 1860, the Loomis Gang reportedly had a network of criminal associates extending from the Canadian border to northern Pennsylvania, and from the Finger Lakes to southern Vermont.

During the Civil War, the Loomis Gang had a new outlet for stolen horses – the Union Army. On October 10, 1864, the Morrisville Courthouse containing indictments against the Loomis Gang, burned to the ground. Wash, who reportedly started the fire, showed up to offer his help in putting it out. On Halloween night, 1865, the Sangerfield Vigilantes Committee, including soldiers fresh from the war organized under the leadership of local constable in secret meetings at Waterville, raided the Loomis farm. In the fight that ensued, Wash was killed, his skull fractured. Another mob attacked the farm the next year, burning the house. After losing the farm to tax arrears soon afterward, Rhoda moved with two of her children – Denio and Cornelia – to Hastings, New York, some 70 miles away north of Syracuse.

Although some descendants of the criminal wing of the extended Loomis family proudly claim descent, others have tried to hide it. Among the Loomis descendants was the poet Ezra Pound (Ezra Weston Loomis Pound). Although raised in Philadelphia, where he attended the University of Pennsylvania, he transferred to Hamilton College (alma mater of blogger Carl) in Clinton, about 16 miles to the north of the former Loomis farm, studying there in 1903-05.

Stories and legends about the infamous Loomis Gang persist in central New York. Some of them have Wash Loomis’ ghost and those of other gang members haunting the Nine Mile Swamp countryside – much of it now drained and converted to farmlands. A road in the region, Loomis Road, bears the family name.