[h=1]A More Mathematical Explanation[/h]

[Click to hide A More Mathematical Explanation]

The information in this section is drawn primarily from the excellent book

Mathematics of the Incas[SUP]

[1][/SUP], which is based upon data taken from studying nearly 200 different quipus.

[h=2]The Incan Number System[/h] The knots on the cords represent numbers. Quipus record numbers using a

base-ten positional system. This is essentially the same as the number system we use, a similarity which is actually quite remarkable. Many civilizations never developed a written number-positional system on their own, and for those that did, the use of base-ten is not a given.

Image 2

Image 2. An image showing the types of knots used in quipus: a figure-eight knot (in blue), a single knot (in red), and a long knot with three turns (in green). Note that these terms differ from the mathematical names for these knots.

Positional systems have an advantage over other numerical systems because they make basic arithmetic much simpler. Imagine trying to do long division with Roman Numerals or tally marks - it's very difficult to do without translating the numbers into a positional system. Although the idea of doing arithmetic with knots and string may seem strange, it's certainly easier than attempting the same with Roman Numerals. The fact that quipus use a positional system is strong evidence that the Incas were familiar with arithmetic[SUP]

[1][/SUP].

[h=3]Base-ten[/h] Unlike the difference between positional and non-positional systems, there is nothing special about base-ten that should make the Incas choose it over any other base. Base-ten means that a number system's library consists of ten symbols. Ours are the digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9, and the Incas' symbols were groups of knots (as described below). People often say that our number system is base-ten because it evolved from counting on our ten fingers, but this doesn't mean that ten is the most "natural" base, or the only one that we would have expected the Incas to use.

Evidence that other bases can evolve naturally can be found in language. Even cultures that never developed a written or recorded number system show evidence of a base system in their number words. In English, words like "fourteen" ("four" + "ten") show that our language evolved around base-ten. Many cultures have similar linguistic markers, but for different bases, and this often corresponds to a different method of counting on their hands. For example, some cultures count the spaces between fingers instead of the fingers themselves, and wind up with a base-four or base-eight system[SUP]

[3][/SUP][SUP]

[4][/SUP]. Some cultures don't count on their hands at all, and count instead by a series of body parts - they may end up with a system that counts up to thirty-something before cycling back (see the interesting video

for more).

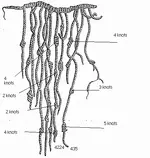

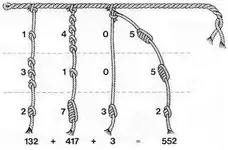

Image 3

Image 3. In this diagram, the main cord is shown in black and the pendant cords are colored. S, E, and L stand for single knot, figure-eight knot, and long knot, respectively.

[h=3]Reading Numbers on Quipu[/h] All in all, it's actually quite surprising that the Incas had an advanced number system, and even more so that it should be so nearly analogous to our own! Because of this, the numbers on quipu are pretty simple for us to learn to read.

As you move from the end of a pendant cord towards the main cord, each successive group of knots represents one higher power of ten. So a cord that has three knots at the top, then two, and then one at the bottom represents the number that is commonly written as 321. Most of the time, numbers are represented using single knots (illustrated in

Image 2), where the number of knots in the cluster corresponds with the digit in that place. In the units place, however, different types of knots are used. Long knots are used for units values of 2-9, where the number of turns represents the value of the units digit. A figure-eight knot is used for a units value of one.

In

Image 3, cords are represented as lines, and knots are represented by a number and a letter (eg 4S means four single knots). In this quipu diagram, three different colors are used, and the values represented are 84, 321, and 9. Notice that, as was stated above, single knots are used in all places other than the units place, while in the units place, long and figure eight knots are used.

It is important to note that the units place on one cord lines up with the units place on the next (and the same with the other places). Because of this, an empty space can be left to indicate a value of zero. So the number 1,003 would be represented by one single knot near the top of the pendant, a large space corresponding with the empty hundreds and tens places, and a 3-turn long knot at the bottom of the cord.

This interpretation of quipus was first proposed by Leland L. Locke at the beginning of the 1900s[SUP]

[1][/SUP]. It is believed that this is the correct interpretation because with it, the values on the top cords of many quipus are the sum of the values on the associated pendants, a pattern that shows so consistently that it must be intentional.

[h=2]Cross-Categorization[/h] The spacing of the cords groups certain classes of information together. When combined with color distinctions, spacing can be used to create complex cross-categorization. Use and placement of subsidiaries can be used to organize hierarchical information. This means that the information represented in a quipu often has relationships that we might represent by a chart or a tree diagram.

Image 4

Image 4. Diagram showing how quipu pendants can be indexed. Corresponding charts are shown to the right.

A quipu that translates to a simple chart is typically composed of several distinct groups of pendant cords, where each group of cords corresponds to a column in the chart, and each cord within the group corresponds to a specific element within that column. The order and color of the cords in the group tells you which row the element goes in. For example, if a quipu consists of three groups of pendants, and each group contains six different colored strings, it can be represented as a chart with three columns and six rows. We can label both the quipu diagram and the chart as a series of elements of the form

, where i=1,2,3,4,5,6 and j=1,2,3 :

| p[SUB]11[/SUB] | p[SUB]12[/SUB] | p[SUB]13[/SUB] | | p[SUB]21[/SUB] | p[SUB]22[/SUB] | p[SUB]23[/SUB] | | p[SUB]31[/SUB] | p[SUB]32[/SUB] | p[SUB]33[/SUB] | | p[SUB]41[/SUB] | p[SUB]42[/SUB] | p[SUB]43[/SUB] | | p[SUB]51[/SUB] | p[SUB]52[/SUB] | p[SUB]53[/SUB] | | p[SUB]61[/SUB] | p[SUB]62[/SUB] | p[SUB]63[/SUB] |

| Of course, we can also construct the table the other way, with rows representing cord groups and columns representing placement and color:

[TABLE="align: center"]

[TR]

[TD]p[SUB]11[/SUB] | p[SUB]21[/SUB] | p[SUB]31[/SUB] | p[SUB]41[/SUB] | p[SUB]51[/SUB] | p[SUB]61[/SUB] |

| p[SUB]12[/SUB] | p[SUB]22[/SUB] | p[SUB]32[/SUB] | p[SUB]42[/SUB] | p[SUB]52[/SUB] | p[SUB]62[/SUB] | |

| p[SUB]13[/SUB] | p[SUB]23[/SUB] | p[SUB]33[/SUB] | p[SUB]43[/SUB] | p[SUB]53[/SUB] | p[SUB]63[/SUB] | |

[/TD]

[/TR]

[/TABLE]

[h=3]Interpreting a Sample Quipu[/h] This section discusses a modern-day quipu that encodes information modified from Excerise 5.2 in Mathematics of the Incas[SUP]

[1][/SUP]. The quipu is shown below:

Image 5

Image 5.

Ignoring the dangle cord for now, the quipu has four groups, containing four, four, three, and four pendant cords, respectively. There are four colors of pendant cords used, one in each group, except for the third group, which is missing a purple cord. This quipu can be described as the set of elements

, where i represents the groups and j represents the pendant colors, and i=1,2,3,4 and j=1,2,3,4. The information can then be organized into the chart seen in

Image 5.

Several patterns can be seen. First, all of the fourth column entries are the sum of the preceding entries in that row. Second, all entries are multiples of twelve, and no entries are fewer than twelve. The two twenty-fives may at first appear to be an exception to the multiples-of-twelve pattern, but when we remember that only integer values can be represented on the quipu, they make sense. When we're trying to divide something without using fractions, we usually deal with the remainder by splitting it up as evenly as possible. For example, if we were to divide 8 pieces of candy between three people, one person would get 2 pieces and two people would get 3 pieces. The twenty-fives tell us that somewhere along the way, we had a remainder of two, and dealt with it by making those two values 25 instead of 24. Finally, we can now see that 242, the value of the dangle cord, is the sum of the entries in the fourth column.

If this were a real quipu, there would be little else to do with it, other than conclude that this quipu, like many others, demonstrates the type of data patterns that are the result of careful planning and not chance. Since this is only a sample quipu, however, the information it encodes is known, and can be used to give meaning to the numbers.

Image 6

Image 6. The sample quipu image relabeled to show what its components represent.

This example is designed to illustrate the results of the distribution of 242 ears of corn among four families. The rule for distribution is that each member of the community gets an equal share of corn, but because no ear is to be broken into pieces, the remainder is split between the two eldest people.

The first family consist of a man, a woman, the man’s two parents, and two children. The second family is a man, a woman, the woman’s sister, and four children. The third family is just a man and a woman, and the fourth family consists of a man, a woman and three children. Each pendant color represents a family. The first group of cords represents the ears of corn given to men, the second group represents the ears of corn given to women, and the third group represents the ears of corn given to children.

Since there are twenty people in the village, the 242 ears of corn divide into 12 ears each with two left over. The blue cord in the first group has a value of 12 because it represents the 12 ears of corn given to the father in the second family. The green cord in the third group has a value of 36 because it represents the 12 ears of corn given to each of the three children in the fourth family. The two extra ears of corn go to the grandparents in the first family, which is why the red pendants in the first two groups show a value of 25 instead of 24. There is no purple pendant in the third group because the third family has no children. The fourth group totals the corn given to each family as a whole, and the dangle cord records the total ears of corn distributed.

Quipus can also be used to record multiple sets of data. For example, if we wanted to record the distribution of corn in more than one village, instead of being its own quipu, the quipu above might be attached to a main cord that contained several similar quipus. Each pendant cord of this new quipu would have subsidiaries that corresponded to charts just like the one we used to interpret our sample. These more complicated quipus have elements of the form

, which correspond to

i related charts, each with

j columns and

k rows.

[h=2]Hierarchical Organization[/h] Quipus can also represent hierarchical information, usually through the use of subsidiaries. The overall description of these quipus is not a plain chart, but a tree diagram, or a chart where some of the elements are tree diagrams. This type of quipu is well-suited to record things like organizational structure or a series of successive choices - information that involves several levels and where each data point has no more than one connection on the level higher than it.

In the example below, the quipu and tree diagram could be used to display the different pricing options of a three-stage journey. Let's say a traveler needs to get from City 1 to City 4 by way of City 2 and City 3. The traveler is trying to choose between taking the train and taking the bus for each stage of the trip, and there are no buses from City 3 to City 4. The diagrams below show the structure of the options available to the traveler, and the prices for each option could additionally be shown by adding numbers.

[TABLE="align: center"]

[TR]

[TD]

----------------------------------Quipu[/TD]

[TD]

---------------------Tree Diagram [/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]

[/TD]

[TD]

[/TD]

[/TR]

[/TABLE]

In both the quipu and the tree diagram, method of transportation is indicated by color. On the quipu, trains are blue and buses are maroon; on the tree diagram, trains are black and buses are yellow. Each cord or line segment is a different stage of the journey, and each connection represents a city.

Some of these hierarchical quipus have subsidiary structures that are consistent and repetitive, demonstrating rhythm, symmetry, and variations on patterns. Some scholars believe that quipu that are repetitive like this use number labels as memory aides in narrative recounting[SUP]

[1][/SUP].

[h=1]Why It's Interesting[/h]Quipus are important because their existence "dispels the notion that mathematics flourishes only after a civilization has developed writing"[SUP]

[5][/SUP]. By using quipus, the Incas were able to do arithmetic and keep incredibly complex records (some quipus are made of hundreds of cords) - tasks which most people assume can only be effectively done in literate societies. [h=2]History[/h]

Image 7

Image 7. A drawing from

Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno, a text that discusses quipu.

[show more]

[h=2]Uses[/h] When interpreted as discussed in

A More Mathematical Explanation, the data found in quipus is very regular. Most quipus show evidence of summation (or of subtraction), and there are often consistent ratios between related categories in the charts the quipus translate to. These patterns convince scholars that the Incas weren’t recording random statistics, like the number of days it rained in a certain village, but data that was the result of carefully planned actions, such as the distribution of food from storehouses[SUP]

[1][/SUP].

All of the numbers found on quipus are necessarily integers, but there is evidence that the Inca had the arithmetical concept of multiplication/division as well as addition/subtraction. Just as many cords or charts contain the sums of information found in other cords or charts, so do many cords contain evidence of numbers being divided into equal parts (or as equal as possible when only integers can be used)[SUP]

[1][/SUP].

There is strong evidence that quipus were also used by Incan storytellers and historians[SUP]

[1][/SUP][SUP]

[2][/SUP], but there is disagreement as to whether quipus can be said to constitute a writing system. Some experts[SUP]

[1][/SUP] have said that quipus are just as much a writing system as cuneiform was in its early years, when it was only used for political arithmetic and record keeping, but that it is unlikely that narrative quipus contained anything beyond numeric labels that assisted in memory recall.

Other scholars have demonstrated that there are Spanish records telling of the existence of "Royal Quipus", which supposedly formed a syllabic system capable of recording language, but these Spanish sources might not be reliable [SUP]

[2][/SUP]. Perhaps the best answer is given by Gary Urton, in his article “Recording Signs in Narrative-Accounting Khipu”, where he concludes that so far, all that is known for certain is that narrative quipus don’t fit the pattern of record-keeping quipus, and that scholars should keep their minds open to an interpretation based on “the syntactic, semantic, and overall grammatical properties of Quechua”[SUP]

[2][/SUP]. In other words, narrative quipus are still not fully understood, and so it is possible that they do, in fact, constitute a full writing system.

[h=1]Teaching Materials[/h] There are currently no teaching materials for this page.

Add teaching materials.

[h=1]References[/h]

- ↑ [SUP]1.00[/SUP] [SUP]1.01[/SUP] [SUP]1.02[/SUP] [SUP]1.03[/SUP] [SUP]1.04[/SUP] [SUP]1.05[/SUP] [SUP]1.06[/SUP] [SUP]1.07[/SUP] [SUP]1.08[/SUP] [SUP]1.09[/SUP] [SUP]1.10[/SUP] [SUP]1.11[/SUP] [SUP]1.12[/SUP] Ascher, M., & Ascher, R. (1981). Mathematics of the incas: code of the quipu. Mineola, NY: Dover.

- ↑ [SUP]2.0[/SUP] [SUP]2.1[/SUP] [SUP]2.2[/SUP] [SUP]2.3[/SUP] [SUP]2.4[/SUP] [SUP]2.5[/SUP] Quilter, J., & Urton, G. (Eds.). (2002). Narrative threads: accounting and recounting in andean khipu. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- ↑ Hinton, L. (1994). Flutes of fire: essays on California Indian languages. Salt Lake City: Publishers Press.

- ↑ Miller, W. & Silver, S. (1997). American Indian languages: cultural and social contexts. University of Arizona Press.

- ↑ Pickover, C. A. (2009). The math book. China: Sterling.

This page was originally adapted from a paper written by Katherine Derosier

If you are able, please consider adding to or editing this page!

Have questions about the image or the explanations on this page?

Leave a message on the

discussion page by clicking the

'discussion' tab at the top of this image page.[[Category:]]

Categories:

Pre-Kindergarten |

Elementary School |

Middle School |

High School |

Higher Education |

Math Images |

Other |

Number Theory

[h=5]Navigation[/h]

[h=5]Search[/h]

[h=5]Browse images by...[/h]

[h=5]Interaction[/h]

[h=5]Create or Edit a Page[/h]

[h=5]Special Resources[/h]

[h=5]Toolbox[/h]

I am just curious...I never had the slightest notion that you were wanting to mean Platinum with it...I always just thought that it meant white gold...hehehe...But what do I know

I am just curious...I never had the slightest notion that you were wanting to mean Platinum with it...I always just thought that it meant white gold...hehehe...But what do I know