You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

JESUIT TREASURES - ARE THEY REAL?

- Thread starter gollum

- Start date

Springfield

Silver Member

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2003

- Messages

- 2,850

- Reaction score

- 1,391

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- New Mexico

- Detector(s) used

- BS

sailaway

Hero Member

- Joined

- Mar 2, 2014

- Messages

- 623

- Reaction score

- 816

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

The Complaints by enlightened reformers and royal decrees interrupted the growth of the devotion to San Felipe at a time when his cult still addressed persistent tension between creoles and peninsulars. By distancing the crown from Catholic devotion and especially from public religion, the monarchy lost its monopoly on moral authority and the ability to call upon the useful mediating function of religious figures.

Franciscans and Jesuits generated many reports and letters dealing with the Japanese mission and the Nagasaki martyrs. Some of this material was reprinted in the Archivo Ibero-Americano. Other documents came from the Franciscan archive of the Province of the Santo Evangelio in Mexico City, the Archivo Cancillería de España and the Vatican Secret Archive.

The Spanish friars clashed, too, with their fellow Christian missionaries, the Portuguese Jesuits. The conflict between the orders, which gave rise to many documents articulating objectives and activities, highlighted the two orders’ incompatible visions of the post-Trent Catholic Church. Starting in the late fifteenth century, however, the mainstream church came under attack from reform-minded officials and new regular orders. Clerics like Cardinal Francisco Cisneros believed that, in general, people of the Catholic Church in Spain were too ignorant, superstitious, comfortable and well-fed.

The Company of Jesus, founded by Spaniard Ignacio Loyola emphasized elements of mysticism, evangelical work and humanism. In his seminal work on meditative prayer, Spiritual Exercises, Loyola drew so deeply from the mystical tradition that he was jailed by the Inquisition for heterodoxy. . As an ex-soldier himself, Loyola envisioned the order as an active and highly-trained unit of priests. Accordingly, he did not require the Jesuits to use a habit or to attend mass. Loyola inculcated a keen sense of duty and obedience to the order’s general in Rome. The Jesuits were also firmly grounded in secular society; they integrated commerce, printing, patronage and politics into their ministry with fewer qualms than other orders.

Luther’s revolt against the institutional church took away the middle ground from moderate Catholic reformers with similar tendencies. Humanists fell out of favor and the Inquisition persecuted the mystically-inspired Illuminist movement. The Inquisition that had developed institutional capacity in processing conversos and Illuminists widened its scope from enforcing tenets of faith to becoming a guardian of Spanish morals.

Between religious wars, internal Church reform and Spain’s prominent support of Catholicism, the Spanish began to consider themselves superior Catholics. Charles V and Philip II arrested Spanish living abroad who might be heretical and bring social contaminants like Lutheranism or homosexuality back with them. Likewise, Philip II distrusted the religious credentials of non-Spanish; he purged the Spanish Catholic church of foreigners and restricted the emigration of clergy from other nations to Spanish colonies.

Realities in New Spain, Africa and India would quickly disabuse missionaries of their cherished dream of a new Jerusalem. Conversion proved neither quick nor easy. Faced with intransigence and apparent barbarity, the Spanish even questioned the Indians’ humanity.Idolatry persisted despite the efforts of missionaries; evangelization seemed to require stronger measures than inspired preaching. Faced with disappointing results and seemingly intractable Indian idolatry, missionaries in the field began to favor stricter physical punishment and embarked on violent campaigns to eradicate idolatry.

The Jesuits parleyed Japanese commercial interests into permission to evangelize on the islands. Their language skills made them useful to both Portuguese and Japanese. The clergymen let it be known in negotiations that they could influence the destination of the Portuguese ship and its lucrative cargo. Using their position as indispensable commercial intermediaries, the Jesuits convinced the daimyo to permit them to proselytize in their territories. Later, the clerics became directly involved in trade, serving as wholesalers, agents and currency speculators. Although the Jesuits introduced a new religion, Hideyoshi treated the order very much like another Buddhist sect. Buddhist monks had a long tradition of militarization, autonomy and intervention into national politics.

As a Dominican and a diplomatic envoy, Juan Cobo represented the composite administration of Catholicism and monarchy of the Spanish Empire in the Philippines. He suggested that the reason no Spanish ship had visited Japan was because the Jesuits held a monopoly on Nagasaki. One of Hideyoshi’s last internal conquests was Kyushu, the home base of the Jesuits in 1586 where he witnessed firsthand the Christians’ power. Upon hearing the Jesuit Vice-provincial boast that he could summon two Portuguese warships, Hideyoshi prepared to take action against the Christian sect. He accused the Jesuits of having propagated a dangerous creed and instilling blind obedience among important daimyos and their samurai. Hideyoshi’s forces destroyed sixty of two hundred fifty Jesuit establishments. After this initial campaign though, the letter of the law was never fully enforced. The Jesuits returned to their missions and commercial projects albeit cautiously. They adopted Japanese dress and restricted their proselytizing to behind doors. By the end of Cobo’s mission in 1593 he had in his hands a retraction of the Japanese military threats against the Franciscans and a personal invitation from the regent permitting ten Franciscan Spanish friars to live in Japan. Since the friars believed that the regent invited them as a Christian counterweight to the Jesuits, they considered that their security depended upon strict separation from that order. The result was to discourage the friars from making common cause with their fellow Catholics. Indeed, the relationship between the Portuguese Jesuits and the Spanish Franciscans slowly deteriorated over three years from polite assistance to outright enmity. These problems expressed themselves in character assassination, accusations of poaching converts and reams of documents.

https://www.lib.utexas.edu/etd/d/2008/conoverc30674/conoverc30674.pdf

So here it is all the trouble was within the Church its self. Both orders telling on each other to the Old World, even making things up? Sounds to me like what each order had to say about the other was like a bunch of old ladies gossiping. No wonder the Indians went back to their old ways and declaring the Whitemans GOD is dead and made of wood. How could an Indian believe in a religion that allowed these actions? This is what caused the King of Spain to remove all but Spanish missionaries.

Sorry so long but a link would not do.

Franciscans and Jesuits generated many reports and letters dealing with the Japanese mission and the Nagasaki martyrs. Some of this material was reprinted in the Archivo Ibero-Americano. Other documents came from the Franciscan archive of the Province of the Santo Evangelio in Mexico City, the Archivo Cancillería de España and the Vatican Secret Archive.

The Spanish friars clashed, too, with their fellow Christian missionaries, the Portuguese Jesuits. The conflict between the orders, which gave rise to many documents articulating objectives and activities, highlighted the two orders’ incompatible visions of the post-Trent Catholic Church. Starting in the late fifteenth century, however, the mainstream church came under attack from reform-minded officials and new regular orders. Clerics like Cardinal Francisco Cisneros believed that, in general, people of the Catholic Church in Spain were too ignorant, superstitious, comfortable and well-fed.

The Company of Jesus, founded by Spaniard Ignacio Loyola emphasized elements of mysticism, evangelical work and humanism. In his seminal work on meditative prayer, Spiritual Exercises, Loyola drew so deeply from the mystical tradition that he was jailed by the Inquisition for heterodoxy. . As an ex-soldier himself, Loyola envisioned the order as an active and highly-trained unit of priests. Accordingly, he did not require the Jesuits to use a habit or to attend mass. Loyola inculcated a keen sense of duty and obedience to the order’s general in Rome. The Jesuits were also firmly grounded in secular society; they integrated commerce, printing, patronage and politics into their ministry with fewer qualms than other orders.

Luther’s revolt against the institutional church took away the middle ground from moderate Catholic reformers with similar tendencies. Humanists fell out of favor and the Inquisition persecuted the mystically-inspired Illuminist movement. The Inquisition that had developed institutional capacity in processing conversos and Illuminists widened its scope from enforcing tenets of faith to becoming a guardian of Spanish morals.

Between religious wars, internal Church reform and Spain’s prominent support of Catholicism, the Spanish began to consider themselves superior Catholics. Charles V and Philip II arrested Spanish living abroad who might be heretical and bring social contaminants like Lutheranism or homosexuality back with them. Likewise, Philip II distrusted the religious credentials of non-Spanish; he purged the Spanish Catholic church of foreigners and restricted the emigration of clergy from other nations to Spanish colonies.

Realities in New Spain, Africa and India would quickly disabuse missionaries of their cherished dream of a new Jerusalem. Conversion proved neither quick nor easy. Faced with intransigence and apparent barbarity, the Spanish even questioned the Indians’ humanity.Idolatry persisted despite the efforts of missionaries; evangelization seemed to require stronger measures than inspired preaching. Faced with disappointing results and seemingly intractable Indian idolatry, missionaries in the field began to favor stricter physical punishment and embarked on violent campaigns to eradicate idolatry.

The Jesuits parleyed Japanese commercial interests into permission to evangelize on the islands. Their language skills made them useful to both Portuguese and Japanese. The clergymen let it be known in negotiations that they could influence the destination of the Portuguese ship and its lucrative cargo. Using their position as indispensable commercial intermediaries, the Jesuits convinced the daimyo to permit them to proselytize in their territories. Later, the clerics became directly involved in trade, serving as wholesalers, agents and currency speculators. Although the Jesuits introduced a new religion, Hideyoshi treated the order very much like another Buddhist sect. Buddhist monks had a long tradition of militarization, autonomy and intervention into national politics.

As a Dominican and a diplomatic envoy, Juan Cobo represented the composite administration of Catholicism and monarchy of the Spanish Empire in the Philippines. He suggested that the reason no Spanish ship had visited Japan was because the Jesuits held a monopoly on Nagasaki. One of Hideyoshi’s last internal conquests was Kyushu, the home base of the Jesuits in 1586 where he witnessed firsthand the Christians’ power. Upon hearing the Jesuit Vice-provincial boast that he could summon two Portuguese warships, Hideyoshi prepared to take action against the Christian sect. He accused the Jesuits of having propagated a dangerous creed and instilling blind obedience among important daimyos and their samurai. Hideyoshi’s forces destroyed sixty of two hundred fifty Jesuit establishments. After this initial campaign though, the letter of the law was never fully enforced. The Jesuits returned to their missions and commercial projects albeit cautiously. They adopted Japanese dress and restricted their proselytizing to behind doors. By the end of Cobo’s mission in 1593 he had in his hands a retraction of the Japanese military threats against the Franciscans and a personal invitation from the regent permitting ten Franciscan Spanish friars to live in Japan. Since the friars believed that the regent invited them as a Christian counterweight to the Jesuits, they considered that their security depended upon strict separation from that order. The result was to discourage the friars from making common cause with their fellow Catholics. Indeed, the relationship between the Portuguese Jesuits and the Spanish Franciscans slowly deteriorated over three years from polite assistance to outright enmity. These problems expressed themselves in character assassination, accusations of poaching converts and reams of documents.

https://www.lib.utexas.edu/etd/d/2008/conoverc30674/conoverc30674.pdf

So here it is all the trouble was within the Church its self. Both orders telling on each other to the Old World, even making things up? Sounds to me like what each order had to say about the other was like a bunch of old ladies gossiping. No wonder the Indians went back to their old ways and declaring the Whitemans GOD is dead and made of wood. How could an Indian believe in a religion that allowed these actions? This is what caused the King of Spain to remove all but Spanish missionaries.

Sorry so long but a link would not do.

Last edited:

deducer

Bronze Member

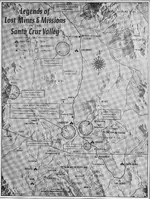

Polzer in the Desert magazine, bemoans sensitive historical sites being destroyed because of "rumors of Jesuit treasure."

Yet he publishes maps such as this, that not only enumerate the myths and their details, but shows where they are. Why would he do this if he wanted to protect those sites?

This, IMHO, sheds light on his remarkably clever strategy- to keep the subject of "Jesuit treasures," within the realms of treasure hunters so that it would never be taken seriously.

Last edited:

deducer

Bronze Member

Postscript:

An excellent argument against Jesuit mines and treasures by father Charles Polzer, SJ, published in the Aug 1962 issue of Desert magazine:

http://mydesertmagazine.com/files/196208-DesertMagazine-1962-August.pdf

<it is a PDF file so you will need a program that can handle that file type, like Adobe Acrobat, and of course the article begins on page 22>

IMHO a poor argument, and one that is misleading and distorting.

Cunning and yet disingenuous of Polzer to equate site destruction with 'rumor of Jesuit treasures.' His continual and persistent association of those two topics seemed to have been a remarkably successful strategy in causing academic or scientific circles to shy away from examining this issue too closely.

Polzer claims that he "wanted" the shovel to be in the hands of an archaeologist, but IMHO, that is the last thing he really wanted. In fact, I suspect he wanted the shovel to stay in the TH'er's hands as he knew they would never be taken seriously.

Last edited:

gollum

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 2, 2006

- Messages

- 6,770

- Reaction score

- 7,742

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- Arizona Vagrant

- Detector(s) used

- Minelab SD2200D (Modded)/ Whites GMT 24k / Fisher FX-3 / Fisher Gold Bug II / Fisher Gemini / Schiebel MIMID / Falcon MD-20

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

- #2,207

Thread Owner

IMHO a poor argument, and one that is misleading and distorting.

Cunning and yet disingenuous of Polzer to equate site destruction with 'rumor of Jesuit treasures' despite a complete lack of evidence. His continual and persistent association of those two topics seemed to have been a remarkably successful strategy in causing academic or scientific circles to shy away from examining this issue too closely.

How is it known that the "destruction" wasn't natural, or engendered by any other cause than treasure-hunting? It was common in the early days for builders to "borrow" material from existing sites.

Polzer claims that he "wanted" the shovel to be in the hands of an archaeologist, but IMHO, that is the last thing he really wanted. In fact, I suspect he wanted the shovel to stay in the TH'er's hands as he knew they would never be taken seriously.

Deducer,

Here is where you are falling a bit short on local knowledge. What I can tell you from what I know about Tumacacori, is that before restoration, the walls had fallen down in some places from being undercut by treasure hunters. Here is an early 1900s picture of some proud treasure hunters trenching right up the the wall at Tumacacori:

Most of the destructive work was done in the early 1900s and during the depression. Polzer was not mistaken on this fact. There was a lot of damage done to several mission sites because of the Treasure Stories associated with them.

Mike

deducer

Bronze Member

Deducer,

Here is where you are falling a bit short on local knowledge. What I can tell you from what I know about Tumacacori, is that before restoration, the walls had fallen down in some places from being undercut by treasure hunters. Here is an early 1900s picture of some proud treasure hunters trenching right up the the wall at Tumacacori:

Most of the destructive work was done in the early 1900s and during the depression. Polzer was not mistaken on this fact. There was a lot of damage done to several mission sites because of the Treasure Stories associated with them.

Mike

Fair enough.

I concede that point.

Oroblanco

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 21, 2005

- Messages

- 7,840

- Reaction score

- 9,877

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- DAKOTA TERRITORY

- Detector(s) used

- Tesoro Lobo Supertraq, (95%) Garrett Scorpion (5%)

IMHO a poor argument, and one that is misleading and distorting.

Cunning and yet disingenuous of Polzer to equate site destruction with 'rumor of Jesuit treasures' despite a complete lack of evidence. His continual and persistent association of those two topics seemed to have been a remarkably successful strategy in causing academic or scientific circles to shy away from examining this issue too closely.

How is it known that the "destruction" wasn't natural, or engendered by any other cause than treasure-hunting? It was common in the early days for builders to "borrow" material from existing sites.

Polzer claims that he "wanted" the shovel to be in the hands of an archaeologist, but IMHO, that is the last thing he really wanted. In fact, I suspect he wanted the shovel to stay in the TH'er's hands as he knew they would never be taken seriously.

Well perhaps "effective argument" would have been more accurate? As in, his article served to DISCOURAGE many treasure hunters from looking for lost Jesuit treasures, the article reads well (well composed) even includes the sad drama of one poor old (and un-named, nor source attributed) Jesuit whom was hard of hearing so walked toward the church only to be "shot dead". Painting the Spanish as vicious, greedy and downright cruel to a bunch of old, harmless "holy men". Whom could not read his article, (having not researched the matter) and not be touched? I agree it is disingenuous, his sloughing off of the "two" incidents where priests were "caught" mining and severely reprimanded, again not cited nor sourced nor are the priests named for that matter, the location somewhere off in the Sierra Madre, which is actually admitting that at least some Jesuits were directly involved in mining.

As to the destruction of the old missions or ruins of missions, it is VERY hard to say how much is simply natural destruction. What treasure hunter destroyed the San Xavier del Bac mission - God? Floods wrecked that one, not treasure hunters. How much destruction was the result of Apache or Seri raiders, or rebelling Pimas for that matter? Then there are another 'class' of treasure hunters, using that term loosely, whom were VERY active in Polzer's time, people who ran around the desert southwest digging for POTTERY. These people were highly destructive, and since most Jesuit missions were in fact Indian villages, it seems very likely that some of the destruction attributed to treasure hunters is really the work of these people out digging for old pots. I spent some time on my last trip to AZ looking over an ancient Indian village that these fellows had ransacked, the damages still clearly visible after decades and it looked like a bombing target range for the number of craters left where formerly were walls of Indian buildings possibly up to a thousand years old.

Anyway I did not mean to imply that I agree with father Polzer, only that his article was, and remains pretty effective at discouraging treasure hunters, and as you said, by keeping the very idea of Jesuit treasure classed in the same realm as science fiction, a "genre" of fantasies, it is even more effective by making treasure hunters themselves appear (by extension) to be dreamers, delusional, chasing rainbows that never existed etc. Not to mention the direct implication of treasure hunters as willfully destructive of historic sites, which many non-treasure hunters reading Polzer's article would conclude. Did you notice the slick way Polzer also shifted mining and treasure onto Spaniards, almost offhandedly? I would imagine father Polzer to be highly pleased with the lasting effects of his article (and other writings) both in helping to preserve mission ruins, and protecting Jesuit treasures that he himself may well have hunted for while he was alive!

My purpose for providing the link to the article was for our readers (whom rarely post) as we have debated extracts from Polzer's article almost from the start of this thread, and as an example of one of the types of resource you can find ONLINE, which would be rather tough (not impossible) to find a paper copy of today. Desert magazine is defunct, a new Dezert mag is now in existence but you can not order back copies of the old Desert mag.

Roy ~ Oroblanco

cactusjumper

Gold Member

Believe it's possible that the old missions had been pretty well gone over by the time Polzer wrote that piece. Beyond that many, if not all were protected sites.

Good luck

Joe

Good luck

Joe

Oroblanco

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 21, 2005

- Messages

- 7,840

- Reaction score

- 9,877

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- DAKOTA TERRITORY

- Detector(s) used

- Tesoro Lobo Supertraq, (95%) Garrett Scorpion (5%)

Hey here is one for our amigo Springfield:

What do you make of that one? A mistake, intending to write Franciscans or perhaps wrote the wrong name, or...? Thank you in advance.

Roy ~ Oroblanco

Report of the Governor of New Mexico to the Dept of the Interior, 1905, published in the US Congressional Serial set issue 4961, pp 523In the Cerrillos district are the Tiffany and other turquoise mines but it was through the discovery of sulphide ores zinc lead and silver that the district came into prominence in 1879. The following year two mining camps Bonanza and Carbonateville were laid out south of Santa Fe. In this district is the Mina del Tierra, the oldest lode mine in the West which was worked prior to 1680 by Indian slaves under the direction of the Jesuits It carries silver, lead, and zinc.

What do you make of that one? A mistake, intending to write Franciscans or perhaps wrote the wrong name, or...? Thank you in advance.

Roy ~ Oroblanco

Springfield

Silver Member

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2003

- Messages

- 2,850

- Reaction score

- 1,391

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- New Mexico

- Detector(s) used

- BS

Hey here is one for our amigo Springfield:

In the Cerrillos district are the Tiffany and other turquoise mines but it was through the discovery of sulphide ores zinc lead and silver that the district came into prominence in 1879. The following year two mining camps Bonanza and Carbonateville were laid out south of Santa Fe. In this district is the Mina del Tierra, the oldest lode mine in the West which was worked prior to 1680 by Indian slaves under the direction of the Jesuits It carries silver, lead, and zinc.

Report of the Governor of New Mexico to the Dept of the Interior, 1905, published in the US Congressional Serial set issue 4961, pp 523

What do you make of that one? A mistake, intending to write Franciscans or perhaps wrote the wrong name, or...? Thank you in advance.

Roy ~ Oroblanco

Yes, I think it's a mistake. All information that we have on the Mina Del Tierra originates with Fayette Jones's New Mexico Mines and Minerals, a standard source written in 1904 to promote New Mexico mining and his own career as a mining engineer. Jones never cited his sources for his description of the old mine's workings, which allegedly was one of the reasons leading up to the Indian Revolt of 1680.

The Franciscans were the Church's presence in early New Mexico, not the Jesuits, and IMO and others', the primary reason for the revolt. Unlike early Arizona - even though the Franciscans' presence was strong and respected by the Spanish - it was the Crown who ruled and controlled things there from the beginning. IMO, Mina Del Tierra was a Spanish mine, not a Franciscan operation. Unfortunately, the archives in the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe were destroyed or stolen after the revolt, so Jones's descriptions of the mine must be taken at face value. His claims that it was the oldest lode mine in the West may be incorrect, IMO, due to circumstantial evidence that allows for the possibility that another deposit in the Santa Rita region in SW New Mexico was exploited 1540 to 1545.

markmar

Silver Member

- Joined

- Oct 17, 2012

- Messages

- 4,308

- Reaction score

- 6,545

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

Springfield

The jesuit map which you posted is interesting . IMO , is close to reality . In the case of the region about Virgin of Guadalupe , Opatas , etc., I give a better (?) location . I shared some cards ( maps ) of this region . For those who have given some attention , is an opportunity to make a clubs straight full .

The jesuit map which you posted is interesting . IMO , is close to reality . In the case of the region about Virgin of Guadalupe , Opatas , etc., I give a better (?) location . I shared some cards ( maps ) of this region . For those who have given some attention , is an opportunity to make a clubs straight full .

cactusjumper

Gold Member

Hey here is one for our amigo Springfield:

Report of the Governor of New Mexico to the Dept of the Interior, 1905, published in the US Congressional Serial set issue 4961, pp 523

What do you make of that one? A mistake, intending to write Franciscans or perhaps wrote the wrong name, or...? Thank you in advance.

Roy ~ Oroblanco

Roy

Let's face it.....When it comes to treasure hunting stories, the Jesuits are just way more sexy than the Franciscans.

Take care,

Joe

Oroblanco

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 21, 2005

- Messages

- 7,840

- Reaction score

- 9,877

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- DAKOTA TERRITORY

- Detector(s) used

- Tesoro Lobo Supertraq, (95%) Garrett Scorpion (5%)

Roy

Let's face it.....When it comes to treasure hunting stories, the Jesuits are just way more sexy than the Franciscans.

Take care,

Joe

Are you contending that the governor of New Mexico, wrote "Jesuits" in his report, because the Jesuits are "more sexy"? Thanks in advance,

Oroblanco

cactusjumper

Gold Member

Are you contending that the governor of New Mexico, wrote "Jesuits" in his report, because the Jesuits are "more sexy"? Thanks in advance,

Oroblanco

Hi Roy,

Which governor are you referring to?

Take care,

Joe

Oroblanco

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 21, 2005

- Messages

- 7,840

- Reaction score

- 9,877

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- DAKOTA TERRITORY

- Detector(s) used

- Tesoro Lobo Supertraq, (95%) Garrett Scorpion (5%)

Hi Roy,

Which governor are you referring to?

Take care,

Joe

Gov George Curry.

Now to answer my question? I asked because the governor's report, had NOTHING to do with any lost treasure or lost mine. Were you suggesting that he wrote Jesuits, because they would be 'more sexy' as it relates to lost treasures?

Roy

PS for anyone interested in reading this report, here is a copy online:

http://books.google.com/books?id=gI...the Interior, 1905&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false

Last edited:

Springfield

Silver Member

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2003

- Messages

- 2,850

- Reaction score

- 1,391

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- New Mexico

- Detector(s) used

- BS

Here's a more detailed description of the mine (based on Jones):

Santa Fe County: The Heart of New Mexico : Rich in History and Resources - Max Frost, Paul Alfred Francis Walter - Google Books (pages 81 & 83)

OT tidbit on Jesuits: per Kenneth Silverman's excruciating biography, Edgar A. Poe lived close to St. Johns College, a Jesuit institution in New York, during the 1840's and knew and spent time with the fathers there. Poe, quite a Christian cynic, praised the Jesuits as "highly cultivated," because they "smoked, drank, and played cards like gentlemen, and never said a word about religion."

Santa Fe County: The Heart of New Mexico : Rich in History and Resources - Max Frost, Paul Alfred Francis Walter - Google Books (pages 81 & 83)

OT tidbit on Jesuits: per Kenneth Silverman's excruciating biography, Edgar A. Poe lived close to St. Johns College, a Jesuit institution in New York, during the 1840's and knew and spent time with the fathers there. Poe, quite a Christian cynic, praised the Jesuits as "highly cultivated," because they "smoked, drank, and played cards like gentlemen, and never said a word about religion."

Oroblanco

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jan 21, 2005

- Messages

- 7,840

- Reaction score

- 9,877

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- DAKOTA TERRITORY

- Detector(s) used

- Tesoro Lobo Supertraq, (95%) Garrett Scorpion (5%)

I guess I don't get an answer this time.

Springfield

Silver Member

- Joined

- Apr 19, 2003

- Messages

- 2,850

- Reaction score

- 1,391

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Location

- New Mexico

- Detector(s) used

- BS

I guess I don't get an answer this time.

It had to be a mistake. Otherwise, the Jesuits would have had to have been 1) openly operating a mine within a few miles of Santa Fe, a Spanish capital and Franciscan stronghold, and 2) active there at least a decade prior to Kino's initial foray into Arizona. Were these guys French Canadian Jesuits? Ha ha.

No. As you say, maybe the 20th century writers said "Jesuit" to juice up the story because of the order's earlier mining reputation. Maybe the writers were good Protesters and used 'Jesuit' as a generic term for all Catlicks. You know - Franciscan, Jesuit - same, same. It's quite a major faux pas, yes, and actually sullies the rest of the story, IMO. Yes, there was Spanish mining in the Ortiz Mountains, but without an explanation of the Mina del Tierra legend's provenance -

I wouldn't bet the farm on the details of the mine described in the previous link I provided.

I wouldn't bet the farm on the details of the mine described in the previous link I provided.Interestingly, some of the 'Padre LaRue' legends, originating in the San Andres/Organ ranges in southern New Mexico, also name LaRue as a Jesuit - more presumed errors, as LaRue (if he existed, that is) was generally tagged as a Franciscan. Just goes to show ya - you can't believe everything you read.

Early 20th century discovery of Spanish ore bags and chicken ladders

from sealed tunnel at Santa Rita del Cobre, New Mexico

Similar threads

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 720

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 3 (members: 0, guests: 3)