The Dr. Thorn mine, the supposed richness of which has caused many a weary step in search of it, is still incognito. We learn from Mr. J. H. Baker, of Salt river, that a party passed that way, some days since, full of hope that they would prove the "lucky cusses" to find it. We wish them luck in the undertaking, and as we are not one of the Job's comforters, we will not suggest a storehouse of disappointment on their trail. We have lived on the frontier for twenty-nine years, and are familiar with fireside stories of fabulously rich mines whose discoverers have withered from the land, leaving no trace of "the find" other than that of its traditional existence.

~

Arizona Weekly Citizen [Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Territory] 28 July 1888 (VOL XVIII NO 28)

------- o0o -------

DR. THORNE'S STORY.

HIS CAPTIVITY BY APACHES AND

FINAL ESCAPE.

His Life Saved by his Professional Skill

Life Among the Indians Discovery

of Gold - His Wanderings

and the Result of a Tiswin Spree.

The true story of the capture of Dr. Thorne by the Apache Indians and his life while held a prisoner among them has never appeared in print, and indeed, the interest in his career among the Indians has heretofore centered solely upon the wonderful discovery of gold it was reported that he had made, to the exclusion of the details of the circumstances that led up to it.

Through the kindness of J. B. Hart, who visited Dr. Thorne at his residence at Casa Blanca three miles above Socorro, New Mexico, in 1881, THE ENTERPRISE is in possession of the story as detailed by the doctor only a year or two before he passed away to his final rest.

In 1852, Dr. Thorne formed one of a party of seven persons, all Georgians, who left Marysville, California, by the southern overland route, to go to New Orleans. They first proceeded to San Diego and there recruited their stock and placed in good order the ambulance and wagon in which they journeyed for the long, tedious and dangerous trip across the deserts.

They reached Yuma without experiencing any adventure or mishap worthy of note and remained a week. They sold their wagon at this place and up on one bright morning in early spring they resumed their pilgrimage with the ambulance and six horses, making easy stages eastward.

Dr. Thorne had come prepared for sickness and accidents and his medicine case and surgical instruments were always convenient and in perfect order and condition. They were well aware of the danger they run in entering the Apache country, but trusted to good luck to escape the vigilance of the hostiles.

Their last camp was made at Gila Bend and the following day promised them safety, for they were gradually approaching the friendly Maricopas and Pimas and every mile lessened the chance of attack by the roaming Apaches. It was late in the afternoon and while yet a long distance from Maricopa Wells, they were suddenly "jumped" by the Indians. It came like a clap of thunder from a clear sky and the surprise was absolute,

At the first shot the driver dropped the reins and fell forward, dead. The horses became frightened and in turning abruptly around, upset the ambulance; the front wheels became uncoupled and when Dr. Thorne, who was inside the wrecked vehicle, raised his head to look out, he saw some of the Indians making off with the horses.

The Indians took Dr. Thorne and one of his companions named Brown and started in a northerly direction, Of the remaining members of the party he never learned their fate, but believed them to have been killed and it was probably the intention of the Indians to make their captives a sacrifice to their love of torture.

After dark a halt was made and both captives were stripped of their clothing and forced to march until near daybreak, when they reached a stream supposed to be the Gila river, where they camped in the thick brush, securely secreted, during the entire day. They evidently feared discovery by the Maricopas and were not anxious for battle with such a superior numbers [sic].

At night they crossed the river and took an easterly course, traveling two days, when they came to a stream of fresh water, timbered with large cottonwoods in a grove of [sic] which they camped. The Indians here made a big fire and by signal smoke informed the scattered members of the tribe where they were located. Three or four days later the Indians began to arrive from all directions with their squaws and children.

In the meantime there was an Indian boy in camp with a broken knee cap from a recent wound, who made a great deal of fuss while a squaw was dressing the wound. The Doctor told an Indian who spoke the Spanish language, that he could cure that boy.

This Indian informed his chief who sent one of his Captains-- who also spoke Spanish fluently -- to summon the doctor to his presence. The chief questioned the doctor as to his ability to cure the wound and was informed that he could amputate the leg with-out causing the boy any pain if he had what was lost in the ambulance. The chief then arose and talked earnestly to the Indians about him and in less than an hour every article taken from the ambulance, even to the bridles and pieces of the reins of the harness was arrayed in a semi-circle before him. Dr. Thorne gathered up all his own effects and found his pocket case and instruments undisturbed.

The following day he administered chloroform to the boy and amputated the injured limb in the most approved manner, and, to the surprise and wonder of the Indians gathered about to witness the operation, the nervous and troublesome lad never moved a muscle under the knife. This remarkable feat at once raised the doctor in the estimation of the Indians to the exalted station of a supernatural being and old chief Pedro immediately ordered his followers to dress the doctor's feet that were cut and blistered from the long walk over rocks and rough ground; had him provided with clothing; a shade built of willows close to his own camp for his own use, and meat cooked for him to eat. The chief even told him that anything he wanted in the way of food that he could get for him, to mention it; that the Indians could not kill him; that he liked him, and then gave to him a strong Indian boy about twelve years old as a servant and body guard. The boy accompanied the doctor from that time on in all his walks about the camp and beyond its limits, but it was soon discovered that he was a spy upon his movement as well as his servant.

The doctor asked the Indians what had become of his friend Brown, from whom he had parted company the first night after their capture, and the others of the party, and they pointed to the west and said they had all gone with other Indians.

They remained at this camp about a month, supposed to be about the mouth of the Verde, and then they moved camp from time to time always towards the east and over a big range of mountains, and during the summer of 1852 they remained in the mountains. In the fall they went in to the valley where another stream emptied into Salt river -- on the north side, and lived all winter. The boy servant and the boy who lost his leg were his constant companions. He taught them to speak English and Spanish and they learned him the Apache language.

The following spring, summer and winter were passed at another camp about two days travel to the eastward and from that stream and between it and the White Mountains they spent four years. The Indians roamed about an area of perhaps a hundred miles square during those four years. They then went back to the first big mountains they had crossed after the boy's leg was amputated, to bury one of their captains, who had died there. All the Indians moved out of that mountain to another high mountain to the eastward, having a superstition that death in a camp portends misfortune.

In this mountain they made a permanent camp. One day Dr. Thorne went out with his two youthful companions to hunt with bows and arrows, and the boy with a willow leg that the doctor had made for him, accidentally stepped into a crevice and broke it. The Indians thought it to be a bad omen and at once moved camp eastward one day's travel, and camped in a cotton wood flat where the Indians planted beans.

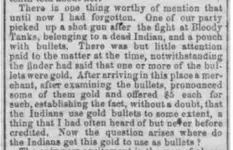

At this camp the running waters of the Salt river could be heard at night. The doctor went out hunting almost every day with one of his companions and on one of these trips the boy picked up a nugget of gold from the bare bedrock in a wash west of some small, very red hills. At this place there might have been perhaps five thousand dollars in gold nuggets in sight. Dr. Thorne was so disgusted with the Indians that he didn't want to have anything more to do with them than was possible and he told the boy that it was of no account.

The young Indian replied that it was good, and that the Indians could get powder and caps with nothing else. Dr. Thorne told him to throw it down; it was of no value, and walked away apparently unconcerned, but from that time forward he took close observations of the surrounding country in order that he might recognize the place again if he ever got free.

After a long residence with these Indians the Apaches and Navajos had succeeded in making a treaty of peace between the two tribes, and the Indians with whom Dr. Thorne dwelt journeyed to the eastern side of the Mogollon mountains to participate in the grand ratification of the event and to complete its conditions. Navajos were to give the Apaches eight hundred sheep for the return of some of their squaws held in captivity, and to forever remain at peace. The meeting was a pleasant one and the exchange was fully completed when, to make the event more memorable a vast quantity of tiswin was brewed and the Indians all got drunk and began fighting. The Navajos succeeded in whipping the Apaches and took away the sheep they had just given them. In the confusion of the melee Dr. Thorne got among the Navajos and subsequently escaped to Cuvero, a little town out from Fort Wingate, and to civilization. He afterwards settled at Casa Blanco, near Socorro, where he married, raised a family of children and finally died in 1882 or 1883.

He made several efforts to find the place where he saw the gold, and bankrupted himself on two different occasions in outfitting expeditions at Socorro to find it. The first time he became snow-blind in the Mogollons and was taken back to his home; on the second attempt the party became disgusted because he could not find it in the White Mountains and would go no further. Some of the old Mexicans in the party contended that they had already gone close to the borders of California and so they turned back when they reached Cibicu creek.

Since that time Dr. Throne was never able to fit out another party in New Mexico, and when the Apache troubles became settled he found himself too old to sleep in the hills and prospect, but was willing to give anybody such information as he could that might assist in its discovery. He told Mr. Hart that he never made an affidavit as to the quantity of gold that he saw; he was familiar with the value of gold in California and to the best of his judgment the amount exposed was worth about five thousand dollars.

He never told Cooley, Woodod [Wood Dodd] or Franklin, as has been stated, that he could load a burro with gold in a day.

This is the story of Dr. Throne. Men have searched time and again for the golden treasure he described; and are still hunting for it, but its exact hiding place is still as great a mystery as ever.

~ Arizona Weekly Enterprise [Florence, Pinal County, Arizona Territory] 5 August 1890 (VOLUME X. NUMBER 1)

------- o0o -------

Dr. Thorne Not Dead.

-------

EDITOR ENTERPRISE : -- In relating to you the “Dr. Thorne Story,” Mr. John B. Hart, my old friend tried and true, inadvertently perhaps, made a few minor misstatements.

I had the honor of writing up certain “reminiscences” recently published in the Prescott (A. T.,) Journal-Miner, and do not now remember making the statement that Doc. Thorne had said, either to Cooley, Dodd or myself,, “a burro” could be loaded with gold in a day. Even had I said so, it would or should have been construed as simply hyperbole, and only that gold was unusually plentiful thereabouts.

Mr. Hart says his interview with Doctor Thorne occurred in 1881 ; that the Doctor died in 1882 or 1883. Now my “reminiscences” were first published in 1890, several years after the alleged death of Thorne. Therefore the foregoing premises being true, how then did Mr. Hart obtain his information? Perhaps this knowledge was obtained from Doctor Thorne (he being dead,) through the medium of “slate-writing” or perhaps “table-rappings.” So much for applied logic.

Notwithstanding my friend’s asserting that the Doctor died in “1882 or 1883,” Thorne has since that time sojourned for awhile in St. Johns, and is now a hale and hearty old man, or he was but a short while ago, residing at the little village of Manzano, in the Manzanita mountains, New Mexico, east of the Rio Grande and about forty miles southeast of Albuquerque. It will be “fresh news” to the old Doctor to hear that he “shuffled off” some six or seven years past.

To be serious however, I am of the opinion the Doctor saw a quantity of pyrites, and at that time, as he says himself, being “partially snow-blind,” it was quite natural for the Doctor to have been mistaken, in what he then saw and took to be gold. As an instance of the deceptive nature of pyrites, my friend Hart will readily call to mind a place in the Santa Catalina mountains, about thirty-five miles, “as the crow flies,” to the east from Tucson, where a ledge of pyrites crosses a small stream of clear water, covering the bed of that stream with a great quantity of yellow nuggets, that ordinarily would likely be mistaken for the precious metal, and particularly to one suffering from partial snow-blindness.

Pesh-be-chee in the Apache language signifies “yellow metal,” and everything seen by Apaches resembling “Pesh-be-chee,” is called gold. This I know from my personal experience with them. Therefore, the bare that that the “Apache boy” said it was gold, and that the Apaches could buy with it powder and caps, carries with it no weight in the argument whatsoever.

My esteemed friend, “Johnny” Hart, is one of the Pioneers of Arizona, and withal an all-round good fellow, and one of the many old pioneers for whom the writer always holds a warm spot in this heart; within the closets of my memory are stored many very many anecdotes and reminiscences of those old pioneers – my friend Hart being amongst the number.

St. Johns, Ariz., April, 1890.

Albert F. Banta

~ Arizona Enterprise (Florence, Pinal County, A. T.) 19 April 1890 (VOLUME X. NUMBER 3]

------- o0o -------

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 27

REMINISCENCES.

Personal Experiences and Recollections of Arizona,

During the Past Thirty-Three Years,

BY A. F. BANTA.

A TYPICAL ARIZONA PIONEER

...On the 12th day of July, 1869, C. E. Cooley, H. Wood Dodd and the writer of these "reminiscences." accompanied by a party of Coyotero Apaches, pulled out of the Pueblo de Zuñi on an unsuccessful search for the fabulous gold placers of Doctor Thorn. Reaching Jack Swilling's ranch on Salt river a little above the

present city of Phenix the latter part of August, 1869; here we camped for two weeks after which each of us three went our several ways. Dodd remained in Arizona and engaged in prospecting, trading and serving the government as guide and scout until 1886, when he was thrown from his horse sustaining injuries from which he shortly afterward died...

~ The Argus [Holbrook, Arizona [Territory]] 12 February 27, 1896 (Vol. I. No. 12]

------- o0o -------

To be continued...

Good luck to all,

The Old Bookaroo

He married Paula Gonzales in Socorro, but he was older and as far as I could tell he had no children with her (but did have a ward).

He married Paula Gonzales in Socorro, but he was older and as far as I could tell he had no children with her (but did have a ward).